Engineers at Georgia Tech have evidence that delivering vaccines via microneedle may be more effective than standard injection against the H1N1 virus. Their study involved giving a vaccine to mice and then subjecting them to the H1N1 virus. Six weeks after given the vaccine, both sets of mice were protected from H1N1, but six month after the vaccine, the injected mice had a 60 percent decrease in antibody production against the virus and extensive lung inflammation. Mice that were vaccinated with microneedles, on the other hand, maintained high levels of protection and antibody production after six months, with no signs of lung inflammation.

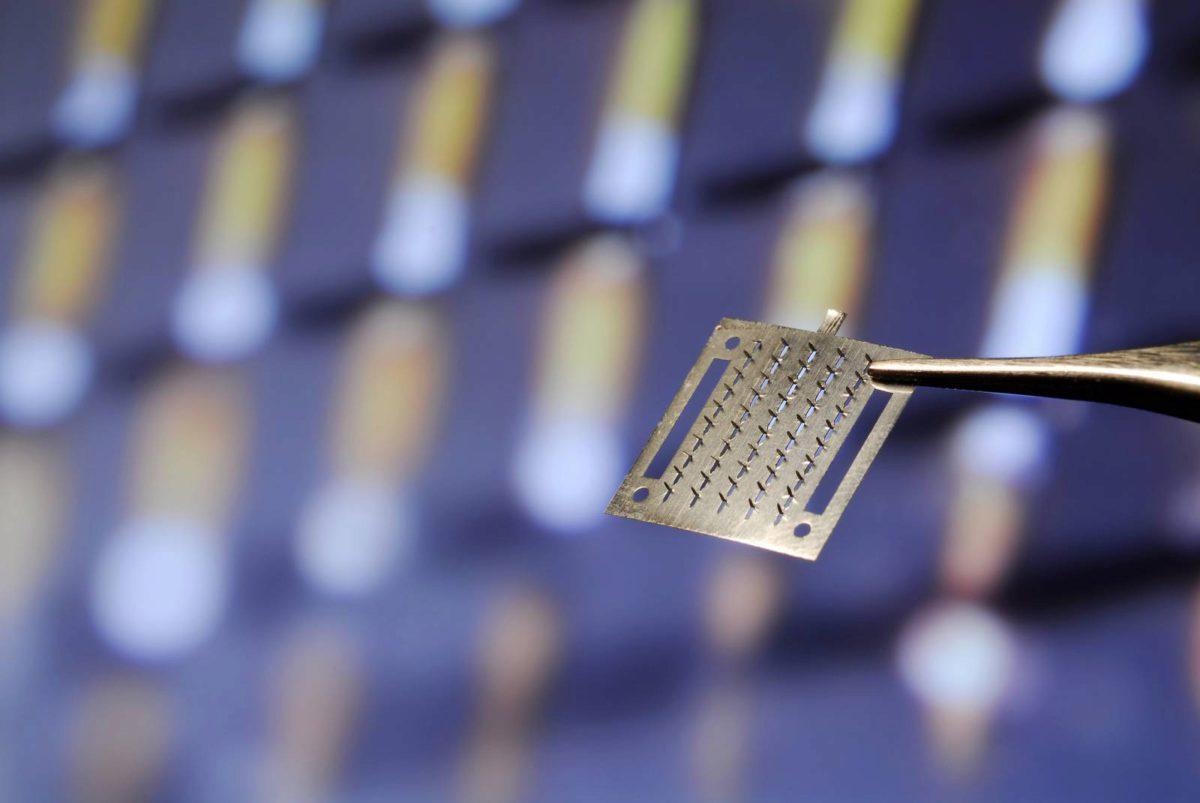

Researchers have already known that intramuscular injection is not the most effective form of vaccination. Muscles have a low concentration of cells needed to relay immune signals and active T-cell response, but skin contains a rich network of antigen-presenting cells, making it ideal for initiating a response. By using antigen-coated metal microneedle patches or dissolving microneedles, the Tech/Emory research team has observed immune responses to the influenza virus that were at least equal to standard injection.

"Microneedle delivery also offers other logistical advantages that make this method attractive for influenza vaccination, such as inexpensive manufacturing, small size for easy storage and distribution, and simple administration that might enable self-vaccination to increase patient coverage,” said Mark Prausnitz , a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.