A new study demonstrates that mechanical forces affect the growth and remodeling of blood vessels during tissue regeneration and wound healing. The forces diminish or enhance the vascularization process and tissue regeneration depending on when they are applied during the healing process.

The study found that applying mechanical forces to an injury site immediately after healing began disrupted vascular growth into the site and prevented bone healing. However, applying mechanical forces later in the healing process enhanced functional bone regeneration. The study’s findings could influence treatment of tissue injuries and recommendations for rehabilitation.

“Our finding that mechanical stresses caused by movement can disrupt the initial formation and growth of new blood vessels supports the advice doctors have been giving their patients for years to limit activity early in the healing process,” said Robert Guldberg, a professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “However, our findings also suggest applying mechanical stresses to the wound later on can significantly improve healing through a process called adaptive remodeling.”

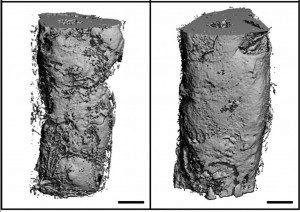

Because blood vessel growth is required for the regeneration of many different tissues, including bone, Guldberg and former Georgia Tech graduate student Joel Boerckel used healing of a bone defect in rats for their study. The experiments showed that exerting mechanical forces on the injury site immediately after healing began significantly inhibited vascular growth into the bone defect region. The volume of blood vessels and their connectivity were reduced by 66 and 91 percent, respectively, compared to the group for which no force was applied. The lack of vascular growth into the defect produced a 75 percent reduction in bone formation and failure to heal the defect.

“We found that having a very stable environment initially is very important because mechanical stresses applied early on disrupted very small vessels that were forming,” said Guldberg, who is also the director of the Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience at Georgia Tech. “If you wait until those vessels have grown in and they’re a little more mature, applying a mechanical stimulus then induces remodeling so that you end up with a more robust vascular network.”

The study’s results may help researchers optimize the mechanical properties of tissue regeneration scaffolds in the future.