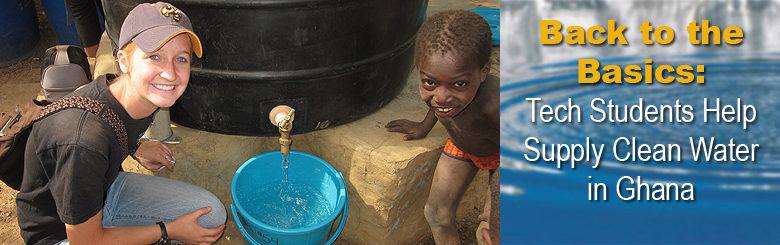

According to Community Water Solutions (CWS) more than 884 million people worldwide lack access to an improved water supply and the problem is particularly severe in Ghana where a lack of clean drinking water contributes to 70% of diseases. Early in 2012 a group of Georgia Tech students participated in a program run by CWS that gave them an opportunity to use their engineering training to address this glaring need. Civil Engineering major Melissa Allardyce was one of those students. Here is what she had to say about the experience.

How did you end up going to Africa and what was the purpose of your trip?

I found out about it through my academic advisor. I went with a non-profit organization called Community Water Solutions. There were 33 college students and young professionals who participated in the fellowship which was a three and a half week program in northern Ghana. We split up into nine teams or three or four people each and our project consisted of building water treatment centers in rural villages. There ended up being six Georgia Tech students on the trip- five of us were from civil and environmental engineering and the other was from chemical engineering. I was really interested in the actual water treatment process.

What neccessitated the building of the centers?

The main problem is that in northern Ghana you can’t drill wells. All of the water in the ground is saline- it’s not potable. Community Water Solutions made a system that allowed the villagers to take their dugout water- the surface water they collect during the rainy season- and treat it with low cost, locally available chemicals. We went in and explained the process to them and told them what we were going to do to help. It took about two and a half weeks to go from start to finish.

What do the actual facilities consist of?

The facility itself is a big polytank with a series of blue drums. The women put the water in the blue drums and treat it with alum- which is a chemical that they can buy in their towns. After they treat the water it sits overnight and the sediment settles on the bottom. That allows them to scoop out the clean water and store it in a polytank. We built stands for the polytanks that allow them to sit off the ground so they can use a spigot. Each family gets one bucket of water and we explained to them that this is clean water for drinking- use it instead of the dugout water.

The process we implemented was incredibly basic- the most basic of basic engineering, and they could barely afford the minimal chemicals that would protect them from all of these water-borne diseases. Before we got there they were using dugout water, which was also used by the cattle and had fish in it. It was just awful water.

Who was responsible for the treatment facilities now?

We trained two women in each village how to maintain the equipment and run the process. Along with the alum, the water gets treated with another chemical provided by CWS which unfortunately isn’t available in the villages. Users pay a very small fee to get water but they don’t mind because they know how important clean water is and the money gets reinvested in buying more chemicals. It functions as a small business for the village.

Was this your first experience abroad? What did you think of it?

It was- I had never been abroad at all. It was really fun. It really opened my eyes to how things are in the rest of the world. You see it on TV and hear about it on the news, but until you actually go there you don’t understand. I know everyone says that, but it really changes the way you look at things. The first few days you’re in culture shock, but it was amazing to see how people lived. They were extremely grateful even though they had nothing. It was great that we could provide them with clean water but they’re still lacking in so many other areas. What we did was a start, but there’s so much more work to be done.

What was the highlight of the project for you?

It was definitely the people. When we got there we met with a whole village. Most of them had no idea we were coming and the kids had never seen white people before- they didn’t know what to think. It was a big village an hour and a half away from where we were staying. When we came back the second day they were playing drums for us and making a big deal of it. There were between 200 and 300 people that came out to see us and circled around us. We spoke to them through our translator and explained to them that we were from Community Water Solutions and that we wanted to give them clean water and that we would be there for three weeks. They were so excited. When we were finished the project the women came out and gave us scarves and performed ceremonial dances around us. They were so happy and joyful. The kids didn’t have shoes, or sometimes even clothes, but they were so happy to have clean water.

Do you see yourself continuing in this line of work after you leave Tech?

I do. I'm doing a co-op in economic development at Georgia Power which is obviously different than economic development in the developing world, but through the rest of my classes and my work I want to focus on sustainability and economic development. I want to stay in that field. I’ve wanted to pursue civil engineering for a long time and I want to use my degree and my training to address the water crisis. I think that’s what I’m interested in and my studies are a perfect fit for it. There are so many good organizations working to meet that need and I want to help.

| Melissa with some of the children from Tamale, Ghana. | Building the polytank stand |

| Collecting water samples from homes. | Testing water samples in the lab |

| 100mL water sample results. Left: clean, bacteria free water. Right: Red dots are coliform and other bacteria. Blue dots are E Coli. Sample was taken from my village's dugout water | Distributing the blue buckets to each household |

| Clean water! | Standing in front of the dugout. |

| All photos provided by Melissa Allardyce. | |