By Michael Baxter

The house is packed. The cameras are rolling. Your name is called, cheers erupt, applause thunders forth from the audience. Out you go, out into the hot lights of the stage and set. You’re on.

The perfectly rehearsed words tumble out in an adrenaline-fueled pitch. With practiced fingers, you manipulate and demonstrate your invention – a device, a contraption, a computer animation. The judges ask why this and when did you that. You answer as precisely and concisely as you can.

Then it’s over. Your seven minutes of TV fame have come and gone.

This is what it’s like for an undergraduate student participating as a finalist in Georgia Tech’s InVenture Prize competition. Having completed its fifth year in spring, the live television event on Georgia Public Broadcasting showcases the best student inventions, most of which are the fruits of future engineers.

But what happens after the lights go down is a much less universal experience. In the weeks and months and years that follow, hopes for market success rise or fall. Students graduate, get jobs, enroll in graduate school, move on. Some pursue commercialization of their InVenture work; others park their dreams or create new ones.

Georgia Tech Engineers caught up with five finalists from past InVenture Prize competitions to ask what happened next. Their stories illustrate the challenges that confront entrepreneurs everywhere – and prove that a College of Engineering education really does venture beyond the classroom.

A Safer Way to Save a Life - Magnetic Assisted Intubation Device (MAID)

If you ever need a breathing tube inserted into your lungs, you’ll want that procedure to go smoothly. And one out of every 10 times, it doesn’t.

Chipped teeth, damaged vocal chords, cuts to the throat — all are the unfortunate results of intubations gone awry. That’s mostly because intubation requires the person performing the procedure to see the trachea and thread a breathing tube through vocal chords, avoiding the esophagus. When that view is obstructed or misinterpreted, injuries or even death can occur.

A student team competing in the 2011 InVenture competition came up with a way to minimize such injuries during intubation. Their product, called MAID, won second place, and it went on to capture top honors in Georgia Tech’s Business Plan Competition as well as a $50,000 grant from the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI). Today, it remains a viable candidate for commercialization.

Intubations are currently performed using a laryngoscope, a device that pries open the passage to the trachea so a breathing tube can be inserted. MAID — which stands for magnetically assisted intubation device — guides the tube in place using magnetic force. A removable, magnet-tipped stylet is placed within a breathing tube, and a strong magnet is placed outside the body, by the Adam’s apple. The pull from the magnet steers the tube into proper position.

“This device has the potential to make quite an impact,” says Shawna Hagen (BME ’12), one of the four students behind MAID. “We get very positive feedback from people in several areas of medicine. Paramedics find it intriguing. So do neonatal respiratory nurses, because intubating an infant can be especially difficult.”

The challenge, says fellow team member Alex Cooper (BME ’12), is getting the market to embrace a new approach to a familiar procedure.

“Everyone who does intubation thinks they’re better than the failure rate,” Cooper says. “It’s amazing how many people have told us that it’ll be great for people who are bad at intubation, but that they’d never mess up the procedure.”

Overcoming such a challenge, he says, will require a business partner with experience in marketing and commercialization. Securing that help as well as venture capital now falls primarily to Hagen, who is employed with GTRI. Cooper and their other teammates, Jacob Thompson and Elizabeth Flanagan, are employed full-time elsewhere.

“We’re currently working with Georgia Tech’s Manufacturing Institute to create prototypes of MAID to be used in efficacy testing,” she says. Further proof of MAID’s value may just get medical practitioners to take a second look.

Watering the World - Tubing Operations for Humanitarian Logistics (TOHL)

Laying a one-kilometer water line across hilly terrain usually takes days. But TOHL can do it in less than 10 minutes.

The student-founded company, a 2012 InVenture finalist, field-tested its water-delivery technology in July of that year. TOHL attached a spool of its high-density polyethylene tubing to a helicopter, placing one end of the tube into a tributary of the Maipo River in Chile. The spool was then flown over the hills, feeding out tube along the way, with the other end dropped in a nearby community.

When water came flowing through, the trial run proved TOHL’s concept: “Mobile infrastructure” for water delivery could be installed quickly after a natural disaster.

The students behind TOHL were inspired to find a new solution for clean water after the devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti. When they presented on the InVenture program, they believed emergency installations would be the heart of the business. Today, that focus has expanded to include installing permanent infrastructure.

“There are still almost a billion people who lack reliable access to water,” says CEO Benjamin Cohen (CE ’11). “They are in a permanent state of emergency. Our goal is to connect those people [to water resources].”

Since InVenture, TOHL has raised more than $500,000 in grants, awards and donations, including $80,000 awarded to Cohen, who was named a 2013 Echoing Green Fellow, and $50,000 from winning the Start Something That Matters contest sponsored by TOMS shoes founder Blake Mycoskie. The media has taken notice, too, with coverage from the BBC, Forbes and Inc. magazines, and the Discovery Channel’s “Daily Planet,” among others.

Cohen and Apoorv Sinha, members of the original InVenture team, remain involved in day-to-day operations. Teammates Melissa McCoy and Travis Horsley continue to work in support roles. They have been joined by fellow College of Engineering alumnus Ibrahim Sufi.

The company’s biggest technical challenge now is to design a spool that can dispense larger tubes that don’t twist as the line feeds out from the helicopter. Figuring out the right spool width, tube diameter and altitude for delivery is “a big optimization puzzle,” says Cohen.

TOHL has operations in Chile, Kenya and Haiti. Cohen predicts that TOHL’s new emphasis on long-term installations will secure multimillion-dollar annual revenues within three years.

Clearer Access to the Inner Eye - AutoRhexis

The number of American who undergo cataract surgery each year now equals the entire population of Philadelphia. And as the nation’s baby boomers age, the procedure is being performed more and more.

While common, cataract surgery presents a challenging step: creating a hole in the lens capsule, a layer of tissue that protects the lens of the eye. It’s like cutting cellophane with a knife. The surgeon makes an incision, then uses tweezers to tear a roughly circular opening to access the lens.

One in five surgical residents botches this part of the procedure, according to estimates. But if engineering alumni Chris Giardina (BME ’11) and Shane Saunders (ME ’10) are successful, those mistakes will rarely happen again.

Giardina and Saunders were members of a six-student team that presented a surgical tool for the lens capsule procedure at the 2011 InVenture Prize competition. Their instrument, called AutoRhexis, captured the imagination of the television audience and was given the People’s Choice Award that year, bringing a cash prize and help with filing a patent.

AutoRhexis is engineered to make a perfectly round incision in the lens capsule with a simple press of the thumb. The concept is certainly novel, but getting it to market reveals just how complicated entrepreneurship can be.

“We’ve put a lot of effort into the blade of the device,” says Giardina. “At the competition, we had a stainless steel blade, which was a good start but didn’t perform as well as needed for a true clinical trial. Since then, we’ve explored other materials, such as flexible alloys and laser-etched diamonds. But the balance between material cost and cutting efficacy is a constant struggle.”

A marketable instrument, he says, must have a blade 1 millimeter in height, fashioned out of material that cuts effectively. It must also be affordable if the device is to be disposable or be able to withstand sterilization if reused.

Addressing the engineering challenges has fallen to Giardina and Saunders, who now run Rhexis Surgical Instruments in their spare time. (Their four InVenture teammates hold a small stake in the company, too.) Another obstacle involves insurance coverage – currently, the surgical step involving the cutting of the lens capsule does not have its own reimbursement code. Thus, keeping the device affordable is crucial.

Still, Giardina remains optimistic about the endeavor.

“Most of these procedures are performed in private practice, so even if there’s a small cost that insurance doesn’t cover, practices may choose to use AutoRhexis to advertise better patient outcomes,” he says.

The business side of the company is in order, including the non-provisional patent filing. What’s needed most is a $50,000 investment, which Giardina says would cover the completion of a final prototype and new pre-clinical testing with animal models.

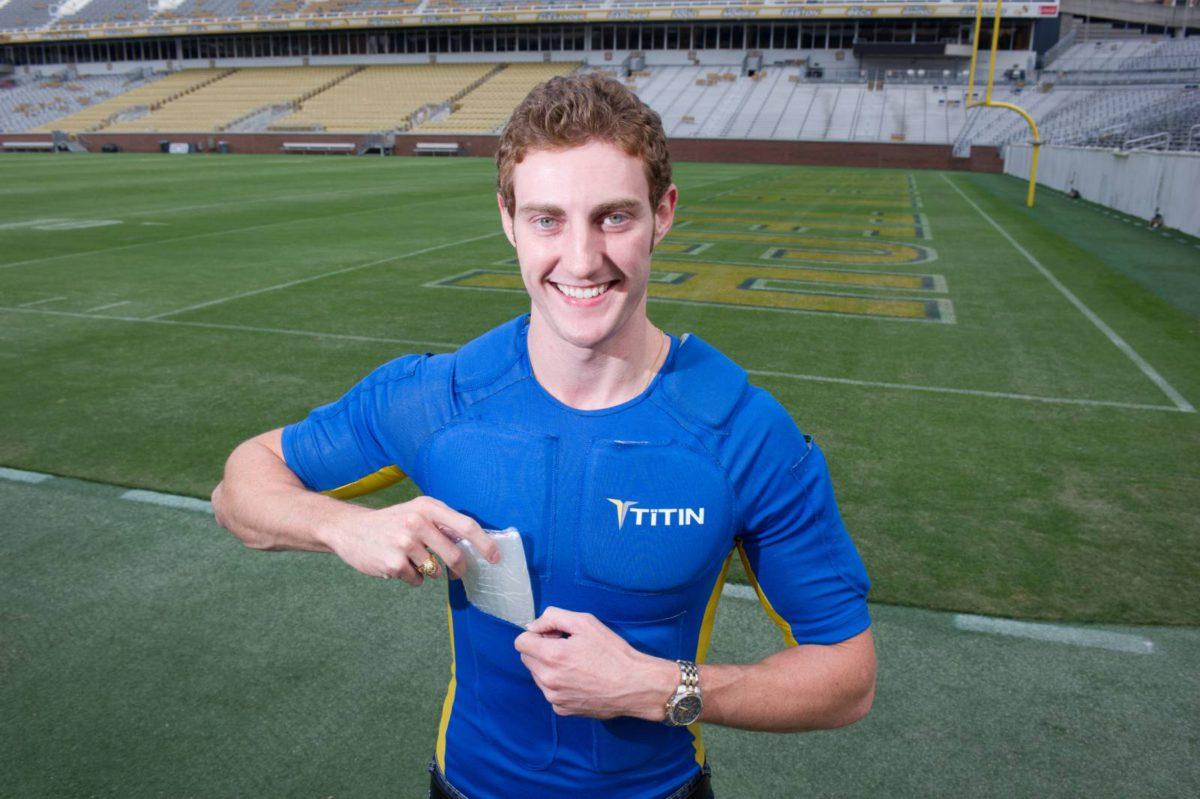

A Shirt That’s Worth the Weight – TITIN

The hallmark of a good exercise shirt is typically its light weight. But Patrick Whaley (ME ’10) turned that notion upside down when he invented a shirt weighing eight pounds.

Marketed under the brand name TITIN, the shirt is designed to add an extra element of struggle to workouts. It’s actually two shirts — one worn underneath, with a pocketed system holding hydro-gel weights; the other worn outside to compress the weights and keep them evenly distributed for the wearer.

Since winning the 2010 InVenture Prize competition, Whaley has been unstoppable in taking his product to the masses.

“I’m expecting to break $7 million in web sales alone in 2014,” he says in a phone interview while waiting to board a flight to Germany, where he would introduce TITIN at a retail exposition. “I’ve got distribution in 13 countries already, and I’m traveling to add others. We’re now selling more shirts in one day than we did in all of October 2013.”

Whaley first had the idea for the shirt as a teenager. He remembers being “a skinny kid who carried extra stuff in my book bag” to gain strength. Thinking there had to be a better way to wear that weight, he began sketching superhero-like shirts.

Georgia Tech gave Whaley the foundation to build upon the idea, and winning InVenture proved to be a defining moment.

“It was really the point of validation,” he says. “After the competition, people acknowledged it wasn’t a hobby anymore. It was a little hard for my dad to let me continue on, because he didn’t want me to lose the opportunity of a college education.”

So Whaley did the opposite: He leveraged his education, managing schoolwork and entrepreneurship with the discipline needed to excel.

“I would do homework sometimes until the middle of the night, then fall on top of the covers, then wake up at 6:30,” he recalls. “It was all business between 6:30 and 8 — if I didn’t do it then, it didn’t get done that day.” Lunches were spent alone, working on the business; a spring break was devoted to vendor meetings. Friends stopped texting Whaley to see if he wanted to hang out.

But the persistence paid off. Whaley’s product won “Most Fundable” in the 2011 Georgia Tech Business Plan Competition and went on to earn prize money in several other competitions. He’s now training his sights on extending the product line, as well as expanding into new outlets and markets.

Anemia Testing Comes Home - AnemoCheck

Millions of people in the U.S. have anemia — or have to be regularly checked for it by a doctor.

The doctor visits are crucial, as severe anemia can lead to organ damage and even heart failure. But they’re also time-consuming and expensive. In her senior year in the College of Engineering, Erika Tyburski (BME ’12) and her senior design team dreamed up a better method of detection: a disposable test people could use at home to check their hemoglobin levels.

Functioning much like the glucose monitoring tests used by diabetics, AnemoCheck requires a mere drop of blood — or less. It’s faster and easier to understand than the quick-turnaround home tests currently on the market.

“The existing rapid diagnostic tests — they call them rapid, but they take 20 to 30 minutes — need three or four drops of blood,” Tyburski says. “They can also be inaccurate because of user error and user interpretation error.”

By contrast, AnemoCheck uses an oxidation-reduction (redox) reaction that takes about a minute to process. Based on hemoglobin levels in the blood, the final result exhibits a color, ranging from blue to red, indicating the presence or absence of anemia.

Since taking second place in the 2013 InVenture Prize competition, AnemoCheck has received $55,000 in additional funding from sources including the Georgia Research Alliance, the Georgia Center for Innovation and Manufacturing and the 2013 Ideas to SERVE competition at Tech, which AnemoCheck won. Tyburski also received a grant from the Global Center for Medical Innovation to develop a prototype device. The initial design has completed preclinical testing involving more than 200 patients, proving its stability and usability and establishing a shelf life.

Now, Tyburski is working on making the color coding more distinct so the test results will be even easier to read. Someday, she hopes to develop an iPhone app to provide foolproof readings. Her efforts are supported by Dr. Wilbur Lam, of the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, and Dr. Siobhan O’Connor of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who both were supervisors on the original project.

The ultimate aim is to form a corporation and begin applying for Food and Drug Administration approval. Beta testing in users’ homes would follow. If all goes according to plan, Tyburski says, AnemoCheck will be on pharmacy shelves in 2016.

Dori Kleber contributed to this article.