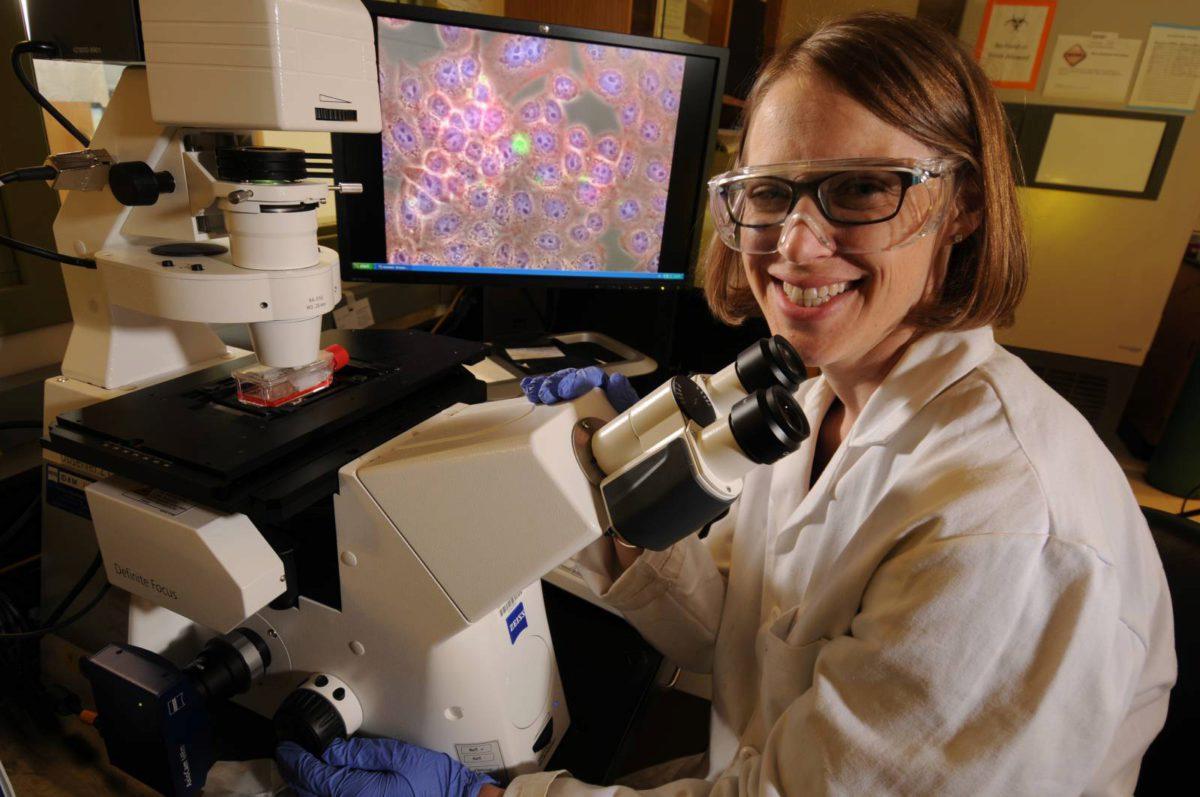

Dr. Julie Champion is an assistant professor in the School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering and is passionate about mentoring young students in a range of settings. In this profile she shares her experience as a female engineer and scientist, talks about her role as a mentor, and delves into her research interests.

Where are you from and where did you go to school?

I grew up in Michigan outside of Detroit. I went to the University of Michigan and got my undergraduate degree in chemical engineering there. I then went to grad school and did a postdoc in California. After that I took a position here at Georgia Tech. I've kind of made a big tour around the country.

What did you know about Georgia before you moved here?

I didn't know a whole lot about Georgia. My best friend came to Georgia for medical school, so I had come to visit her once, and I thought that Atlanta was a nice town. My husband is from South Carolina, so I kind of generally knew about Southern food and that sort of thing.

What is the main focus of your research?

We do what I call therapeutic materials, so the idea is that you might have a protein that could be a therapeutic drug and the challenge of proteins as drugs is that they are very sensitive. They are large three dimensional molecules, and if they lose that three dimensional structure they lose their function. It's very difficult to deliver a protein in the body and keep it from losing that structure, and because it's very large, it's hard to actually get the protein to go where you want it to go. For example, proteins generally don't go inside of cells. So in my lab we try to develop delivery strategies for protecting proteins and getting them to go, for example, inside of cells where they could have their therapeutic function. We take the therapeutic protein and we form it into something like a nanoparticle on its own. Instead of trying to bring in polymers and other materials, we actually induce the protein itself to form the nanostructure that will help protect it and deliver it.

Are there specific illnesses or diseases you are targeting with these treatments?

In general we're looking at immunomodulation, but some of the specific applications that are going forward are inflammatory bowel disease and breast cancer, as well as influenza vaccinations. Those all have immune components and we'll often work with collaborators, especially at Emory, who are disease experts. We're more experts in the protein materials and the fabrication.

Engineering and many of the scientific fields have been dominated by men, although women make up a larger percentage in the life sciences. What has your experience been like as a chemical engineer who works on the bio side of things?

Being in chemical engineering, I've seen both sides. When I was an undergrad in Michigan, half of my class was female and I had three professors who were female. So I thought being a woman chemical engineer was a totally normal thing. Then I got to grad school and I was the only girl in my class, and there were no female faculty at all. I thought that was weird, because I assumed the first thing I experienced was normal. For me it was actually strange that this place didn't have a lot of women chemical engineers. I think if I had had the opposite experience it would have been much more difficult, but I was already comfortable and confident as a chemical engineer. Occasionally you hear comments like "The only reason you got that fellowship is because you're a woman." Basically it comes down to their insecurity and you just have to be confident in your own skills. Nobody wins fellowships only because of their race or gender, or whatever. You have to be confident in yourself first. Nobody is going to give you that confidence. You have to be confident in your own abilities and then what you win, or what you achieve, or are recognized for beyond that is because of your abilities, and not only because of who you are.

Do you notice a difference between your male and female students in terms of attitude?

The thing I notice the most about female students is a lack of confidence. They wonder if they belong here and if they're good enough, and nobody is going to give that to you. You have to find it in yourself. That's the main thing I've learned and that I try to pass on to the students I mentor and teach.

Talk about your role as a mentor.

I do it in two roles. I mentor my PhD students on a daily and weekly basis both personally and scientifically. Then for the undergraduate students it's not something I'm doing constantly, it's more at certain times of the year. There's a small handful of them who work in my lab as undergrads, so I am mentoring them constantly, and I really like that part of my job. I get to help them grow and mold them into whatever they want to be. As far as standard mentoring, I mentor the biotech track chemical engineering students whose last names start with C and D. There's only a handful of those in a given semester, and that role has more to do with introducing them to what chemical engineering is and what jobs they may be able to get as well as trying to make sure they have a plan while they're here at Tech. Some of them come back and see me a lot and I mentor them the whole time they're here at Tech, and others check the box, turn in the form, and I never see them again. I'm happy to meet with them as much as they want. Some of them find it useful and others know what they want and they just do it on their own, and that's fine.

What do you do to support the activities of Women in Engineering (WIE) on campus?

One of our big events every year is TEC Camp every summer. That's Technology, Engineering, and Computing camp, and it's for about 40 sixth and seventh grade girls. We do one of the laboratory modules in our lab where they learn about drug delivery. They come for about an hour a day over the course of the week and we teach them how to crystallize drugs, how to make drug delivery particles, how to get their drugs in those drug delivery particles, and how they would release. They're really doing hands-on experiments the whole time, and they really seem to like it because they can make stuff. We try to make it as fun as possible. We add color so they can actually see what's happening. Part of the problem when you're talking about what we do is that we're making particles for the body that are so tiny you can't see them. We make larger versions for the class so they can see them and hold them and try to understand what they're doing.

My grad students like it a lot too. It helps all of my grad students, male and female, to get involved teaching these girls about research and giving them a taste of science and engineering in. The students get to see if they're interested in teaching and that's not an experience they may get otherwise.

What do you like the most about working at Georgia Tech?

I love the people here that I get to work with. My students are excellent, and they're not just good researchers, but they're nice people. I get to share my knowledge with them but they bring a lot of their own ideas. Watching them grow from new engineers to being experts in their area, even more expert than I am, is rewarding and exciting. On the teaching side it's the same thing. The students who come to office hours with questions actually want to know the answer. They're not just sitting in class trying to absorb everything. They actually wondered about something and they care enough to follow up about it. I love interacting with students who want to learn and do well. It makes me feel like my job is important and I'm helping people. If our therapeutics never cure anybody I know I've still helped enable the new generation of engineers.

I enjoy tracking my students and hearing what they've done after they've left Tech. have several students who are now in PhD programs, one who is in medical school, one who is in dental school, and a whole handful who have gone on to take positions in industry. They write to me and tell me how they're doing, even if it's been a few years since they graduated. It's a lot of fun to keep in touch and hear what they're doing. It's very rewarding.