A spinoff of the InVenture competition invites (really) young engineers to design inventions.

A video opens on a scene in a school classroom. Five late-elementary age students, ranging in height from very small to only slightly less small, stand in a row. The video serves as their pitch for an invention they dreamed up.

The kids start firing questions with an enthusiasm otherwise found on early morning infomercials: “Do you hate wearing your helmet?” one student asks. “Have you ever decided to not wear your helmet and then gotten an injury? Does your head get cold when you’re riding your bike in the winter?”

“If you said yes to any of these questions, our invention is for you!” the student exclaims. And then, all in unison, “Safety… Safety… SAFETY!” The group members hold their arms out like actors in a Broadway musical.

This is the beginning of just one of dozens of pitches reviewed by Roxanne Moore, a research engineer who heads Georgia Tech’s K-12 InVenture Challenge, held in March each year. The competition is a grade-school spin-off of Tech’s InVenture Prize, the nation’s largest invention competition for undergraduate students.

In the K-12 Challenge, teachers from elementary, middle, and high schools throughout the state are invited to cultivate innovation in students, facilitating projects worked on either while in school or in extracurricular settings. Schools are invited to send at least one team to Georgia Tech for the spring competition, where winners are chosen at the elementary, middle, and high school levels for first, second, and third places. Awards are also given for “People’s Choice,” as well as best use of manufacturing and IronCAD (Computer Aided Design) software

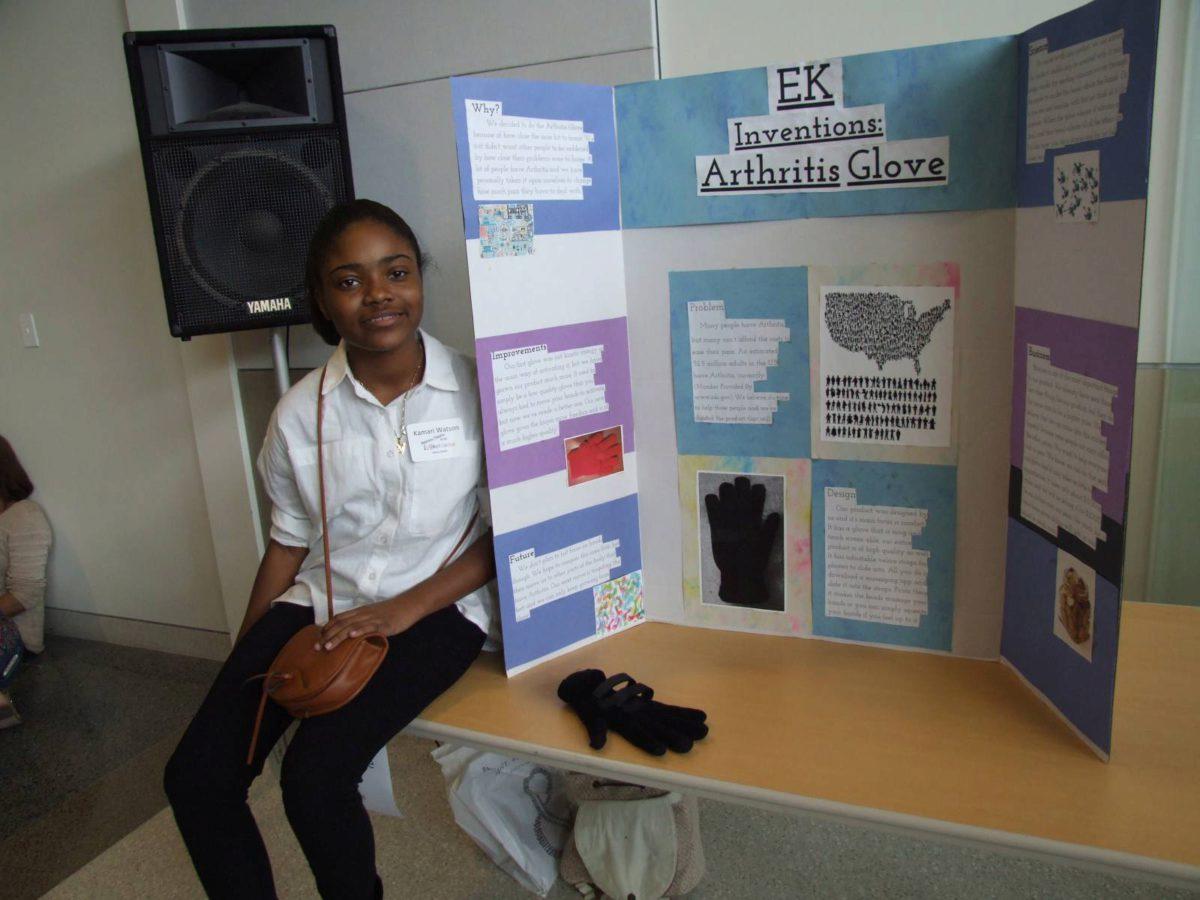

This year’s event hosted 60 teams from 31 schools — over half of them elementary schools — from 12 counties in and around Atlanta. Winners included “The Succulent Solution,” a mechanism that extracts liquid from inside a cactus to be used for medicinal purposes; “Wheel Barrel,” a portable water filtration system inspired by sanitation needs in Sudan; and “Noise X,” noise-isolating headphones that eliminate distracting sounds for students with attention deficit disorders.

Student projects are judged by industry experts and Georgia Tech faculty members on a range of factors including practicality, design-based thinking, marketability, and social responsibility.

This early exposure to engineering and entrepreneurship has played a powerful role in students’ lives. Nick Rupert, now a freshman at Georgia Tech, is a K-12 Challenge winner from last year. Rupert and his collaborators plan to make their winning project — an app that helps chemistry students “visualize both abstract and invisible content”, bringing scientific studies to life on the screen—publicly available by this fall.

For Angelique Johnson, another K-12 Challenge winner, the experience offered a “different type of opportunity” to be creative and tackle a problem otherwise unavailable in typical high school curriculum. Johnson also went on to attend Georgia Tech, attributing a large part of her choice to do so to her interaction with the school through the K-12 Challenge.

The competing students’ pitches are taken seriously — students even get to meet Tech President Bud Peterson — and are critiqued by industry officials and professors. One of Rupert's app’s first critics, a Georgia Tech professor who judged his K-12 Challenge, is now Rupert’s research advisor.

“You build confidence early and repeatedly around an experience that feels technical in some way, or feels entrepreneurial in some way,” says Roxanne Moore. “The more you can create that kind of positive experience, the more a student can self-identify into that type of goal.”

For Moore and others at the Center for Education Integrating Science, Mathematics, and Computing (CIESMC), it’s important to use the K-12 Challenge as a way to increase diversity in science, technology, engineering and math fields. She says that gender diversity is notably more present at the elementary school level, where they see a lot more female inventors at the annual competition.

She tells a story of one group of girls who wore suits to the K-12 Challenge and brought business cards with their titles — chief executive officer, of course — printed.

“They’re just super confident,” Moore says of the girls she sees at the competition. “They haven’t developed a preconceived notion of what they can or can’t do, or be.”

Jeanette Phillips teaches at North Oconee High School, which has sent a winning team to the Challenge for two of the three years it’s participated. Phillips will retire this year, but she plans to continue facilitating the school’s involvement in the K-12 Challenge.

The competition is “educator heaven”, she says, explaining how watching students choose a problem and invest their time and creativity into finding a solution has been a highlight of her professional career.

Though the number of schools and teams has doubled each year since the competition’s inception in 2013, Moore has dreams of expanding the K-12 Challenge even further. Currently, most of the schools that send student teams to compete are in the metro Atlanta area, but Moore would like to see students coming from more rural areas and from more middle and lower socioeconomic backgrounds as well as higher ones.

Ultimately, Moore says, proponents of engineering and STEM need to be creating messaging that appeal to more people. For her, this means showing people that engineering is, at its core, human-centered—a “very broad and really flexible toolbox” for tackling problems humans come across.

“Engineers are totally focused on problems that affect people and affect their lives and affect society, but that’s not always clear when you’re taking thermodynamics, or when you’re taking algebra,” she says.

When asked why it’s important to maintain a K-12 version of InVenture along with the original challenge for college students, Jeanette Phillips puts it simply:

“Why wait?”