Small satellites that make up RANGE will allow researchers to demonstrate new applications and technologies at an all-new level.

Monday December 3rd 2018, a much-anticipated SpaceX launch sent the Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering's cubesats into low Earth orbit. Though several cubesats from the Georgia Tech Aerospace Engineering School have been approved for eventual deployment, RANGE will be the first one to make it into space.

The Ranging and Nanosatellite Guidance Experiment (RANGE) is a prime example of a modern class of small satellites that is allowing researchers to demonstrate new applications and technologies at a level not possible 5-10 years ago. More than 60 other cubesat missions had been scheduled to launch with the Falcon 9.

Hear all about the launch from Brian Gunter on the latest episode of The Uncommon Engineer.

Aerospace Engineering professor, E. Glenn Lightsey, the director of GT's Space Systems Design Lab (SSDL), said the RANGE delay does not put any sort of damper on the AE School's space ambitions.

"In 2019 or early 2020, we expect to be launching another cubesat that Dr. Gunter has worked on, TARGIT, and that will be followed by the launches of Prox 1, RECONSO, MicroNimbus, and others. The Daniel Guggenheim School knows that cubesats are going to be revolutionizing the way we explore and conduct science in space. Cubesats will provide terrific teaching opportunities for budding engineers and they will advance the agendas of the burgeoning space economy. That's why the School has aligned our research and teaching to support cubesat development."

Lightsey's vision is backed up by Mark Costello, the William R. T. Oakes Chair of the AE School.

"The Guggenheim School will continue to build our program to pursue our space research in space," said Costello.

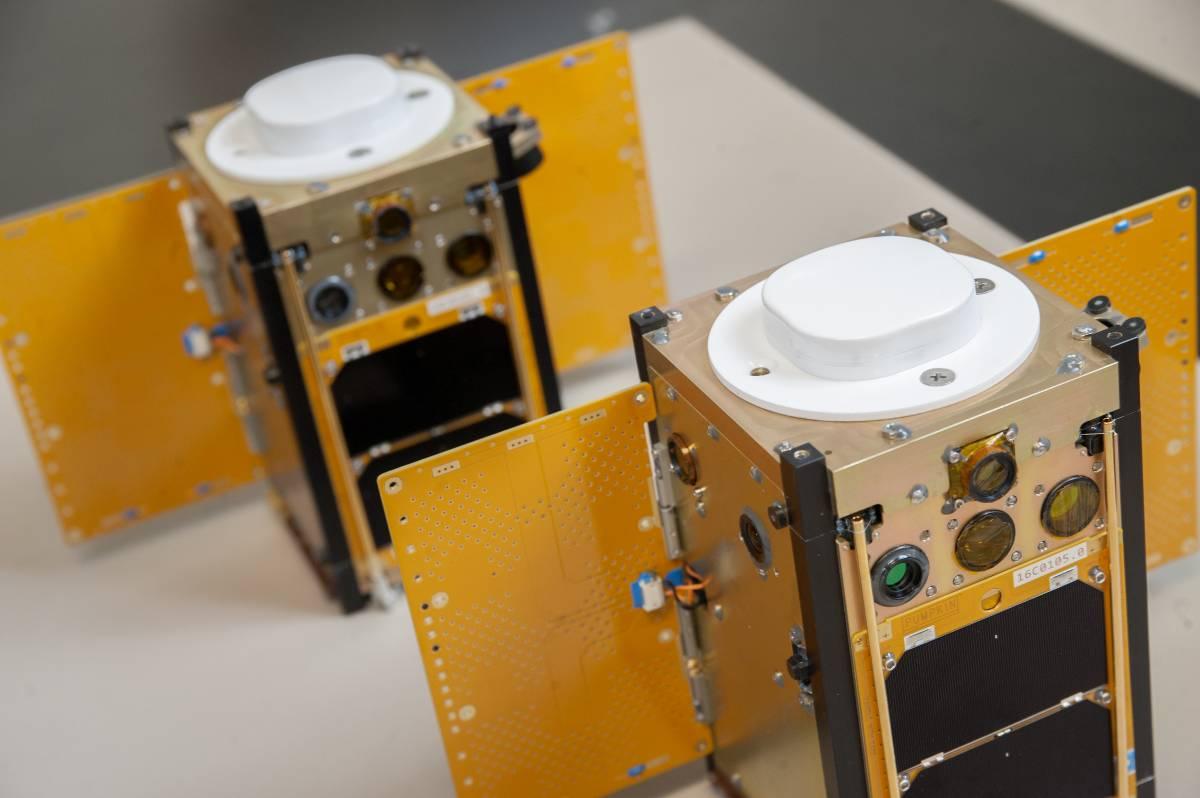

The RANGE mission consists of two 1.5-unit sized cubesats that, together, are about the size of a loaf of bread. Once launched, they will follow each other from a distance of up to 500 kilometers in a leader-follower formation. Ultimately, the mission seeks to collect data that will dramatically improve the capacity for controlling small-satellite constellations or formations.

Where current technology allows researchers to predict asset positioning down to a few meters, RANGE will use an on-board GPS receiver to establish centimeter-level absolute orbit positioning. The results will be verified with ground-based laser ranging data from the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL).

The relative position of the satellites will be measured by a new LiDAR ranging system paired with the first flight of a miniaturized atomic clock that should provide centimeter to millimeter-level range observations out to a 500 kilometer separation distance. The LiDAR ranging system will also double as a low-rate optical communication system, and the mission intends to be one of the first to demonstrate cross-link laser communication between cubesats.

"The satellites will have no on-board propulsion, so they will use differential-drag techniques to maintain the formation, for which very little experimental data exists in the literature," says Gunter. "Additional experiments will be explored involving relative navigation and autonomous maneuvering."

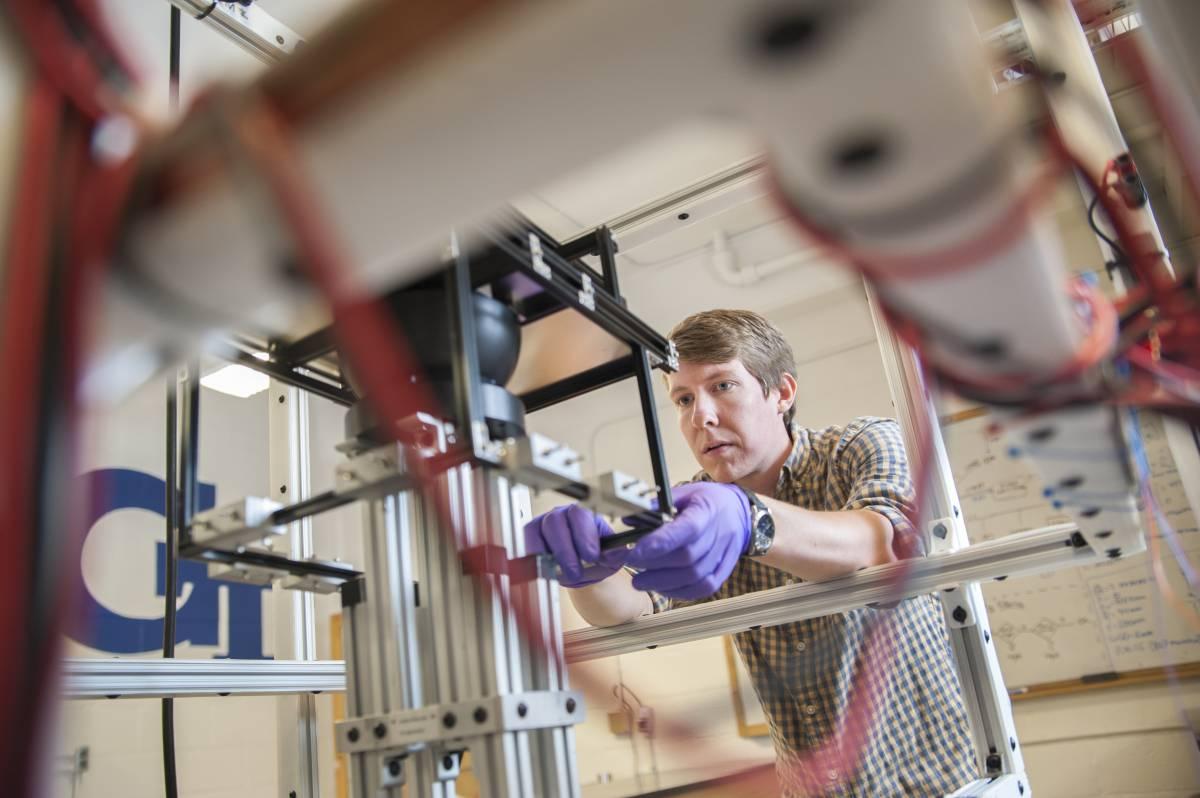

Gunter and Lightsey are confident that launch issues will eventually be resolved for RANGE. Both agree that much of the mission's value came on the back end, where dozens of students spent countless hours planning, designing, prototyping and testing the tiny satellite. There are literally hundreds of specific design, performance, and safety requirements that the young researchers had to meet during several stages of planning. Each failure produced new knowledge that they will not soon forget.

"The launch provider is not concerned with whether your cubesat fails when it's up there, they just want to make sure any failure doesn’t damage another mission, so the design regulations are exhaustive. Even if it's well-built in the lab, there are lots of conditions - violent vibrations from the lift-off or intense temperature variations for instance - that can change the way everything works," Gunter said.

"We ran a number of tests on shaker tables to mimic the vibrations of launch, and with the thermal vacuum chamber to mimic the lack of atmosphere in space. But what you find is, one small oversight - a bad solder joint or a small electrical component fails -- and the whole spacecraft can stop working. This happened to us on several occasions, and is why the testing and development process is so involved. Once the satellite is in space, we can’t touch it anymore, so we have to make sure it is as reliable as we can make it before launch."

Gunter is confident that any other potential problems have been anticipated by his team, which has pulled numerous all-nighters to thoroughly research and test RANGE's capabilities. Hence, once it's launched, RANGE will become a great source of data for future cubesat projects, some of which are in development now.

Launch Details

- Launch of 64 cubesat payload from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

- Monday, Dec. 3 at 1:30 p.m. (EST)

Launch Watch Party

- Begins at 1:10 p.m.

- Guggenheim 442

- Refreshments served