Gabe Kwong’s research focuses on engineering immunity to transform human health

For patients undergoing transplant surgeries, there is always the immediate concern of the body rejecting the new organ – be it a lung, kidney or heart. There are a few different ways the body can reject an organ, one type being T cell mediated rejection. T cells are immune cells that recognize diseases, or in this case foreign organs, and attack because they sense a danger to the body. In the worst case scenario, the newly transplanted organ is rejected, leaving the patient back at square one.

Traditionally, to track and manage T cell response to organ transplants, also known as grafts, a biopsy is done to look at the tissue to monitor the health of the graft. These biopsies are highly invasive, using large needles that can lead to pain and excessive bleeding. They are also just a moment-in-time static snapshot of the health of the graft. That’s where Gabe Kwong’s research comes in with his Laboratory for Synthetic Immunity.

“What you really want to know is patient trajectory,” said Kwong, associate professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech. “With traditional biopsies, you don’t know if the transplant organ is getting better or if it’s going to get worse. The non-invasive platform that we are developing measures T cell activity. If T cells are being overactive, you can track that with our miniaturized biological sensors that probe the graft for early signs of transplant rejection. Our approach is a noninvasive solution to the biopsy.”

An Immunoengineering Lab

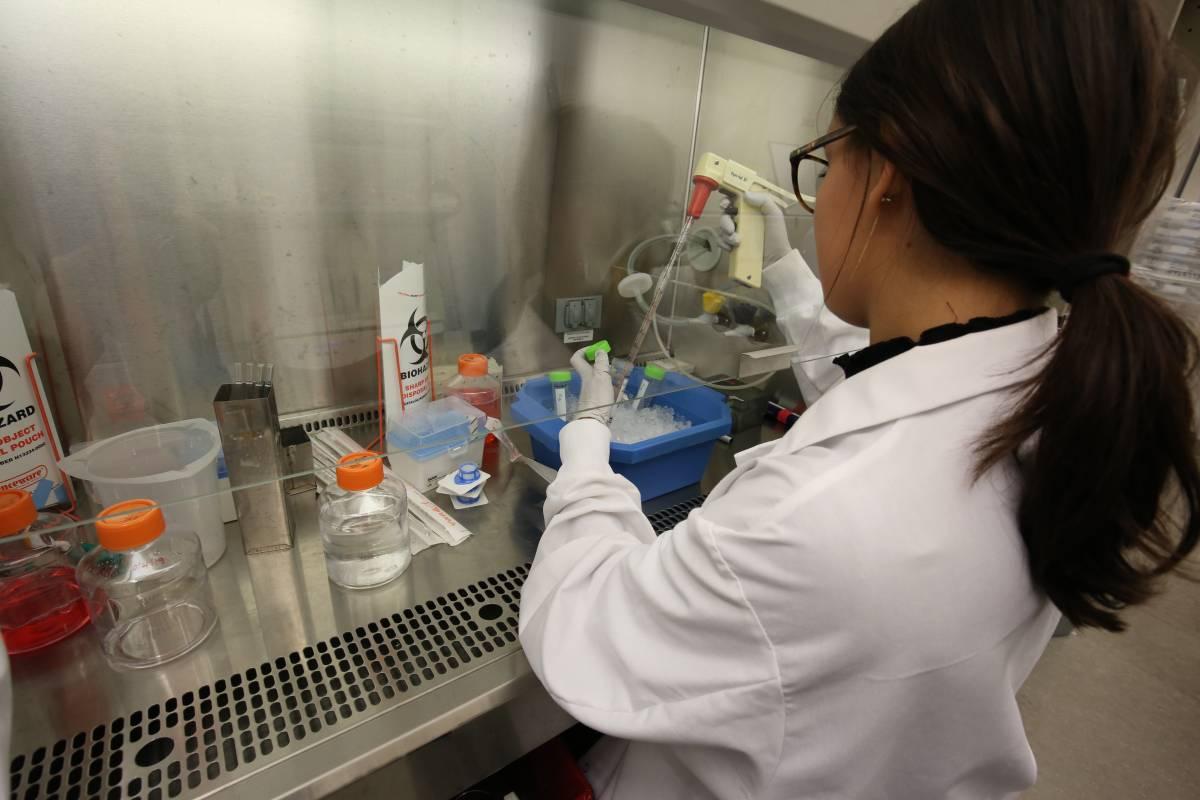

One part of Kwong’s lab is focused on immune sensing, like the T cell sensor for organ transplants, but his work goes further, including engineered T cell therapies for cancer.

“An exciting area of my lab is designing next-generation T cell therapies,” said Kwong. “We treat them like a living drug, a smart drug, because those T cells know where to go, can recognize tumor cells, and kill them.”

Although T cell therapies have the potential to cure patients of disease, a major challenge is that tumors have the uncanny ability to evade immune recognition and even set up a suppressive environment that turn-off T cells once they arrive in the tumor.

When a T cell moves into a tumor to try to suppress it, the tumor will switch off the T cells’ cancer-killing abilities. To address this, Kwong is developing remote-controlled T Cells that leverage a light beam to control the T cells and turn them back on. The first-generation platform involves making the T cells sensitive to local increases in heat.

“You can use the laser light to heat a tumor and then communicate with the T cells and see if you can make them kill tumor cells better,” explained Kwong. “In preclinical models, we are able to induce durable and curative responses.”

Commercializing Technologies

Kwong’s work isn’t happening in a vacuum. In 2015, he co-founded a company called Glympse Bio with the goal of transforming disease monitoring and treatment response. Glympse creates sensors designed to replace the biopsy, with the first focus being on liver biopsy. Recently, the company had its first human trials on healthy volunteers.

According to Kwong, with liver fibrosis or fatty liver disease, drug responses aren’t instantaneous. With oral drug therapies, it can take months to see any sort of potential change in the progression of the disease. For pharmaceutical companies, they still rely on a liver biopsy and sometimes don’t know for months or even up to two years if the drug works and is ready for mass consumption. This is one of the reasons the drug approval process takes so long. But Glympse is trying to change that.

“The long-term goal of the company is to create products that are non-invasive, replacing the biopsy,” said Kwong. “That should help pharma accelerate drug trials. The sensors we are creating have the potential to be predictive so you can get a read out within two weeks of the state of the patient versus waiting twelve months for a biopsy read to determine patient response to drugs.”

Kwong is dedicated to his research, with a passion that started as early as his undergraduate education at UC Berkeley. And it makes him an uncommon engineer as well, given his dedication to the long-term, tireless work that immunoengineering requires.

“You have to be at the top of your game the whole time, and be exceedingly patient,” said Kwong. “The timeline for translational research in the life sciences is long, and you aren’t going to get instantaneous results. But in 10 years of working with this technology, I haven’t lost my drive or passion, and it hasn’t gotten less interesting.”