New ventilator to help developing nations battle Covid-19

With global cases of Covid-19 on the rise, many developing nations lack access to healthcare and the medical infrastructure to help those suffering from the virus. It’s critical that low-cost medical devices with parts that can be locally sourced are available to these countries – devices such as ventilators, respirators and a wide variety of PPE.

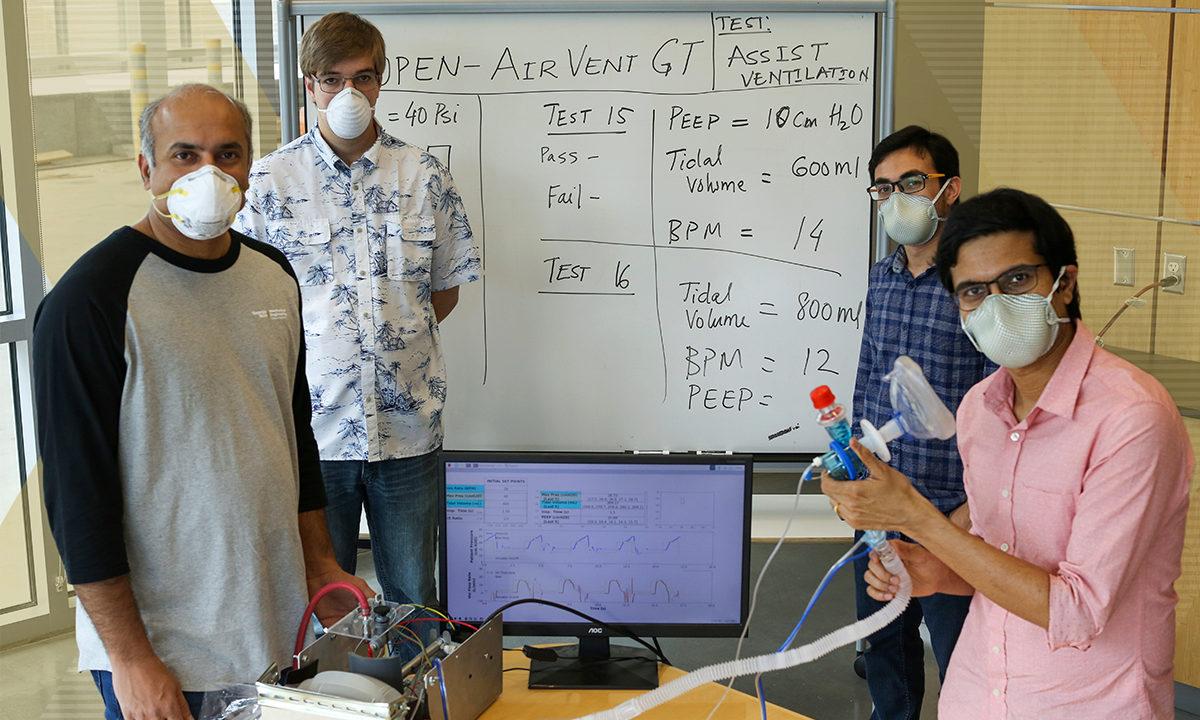

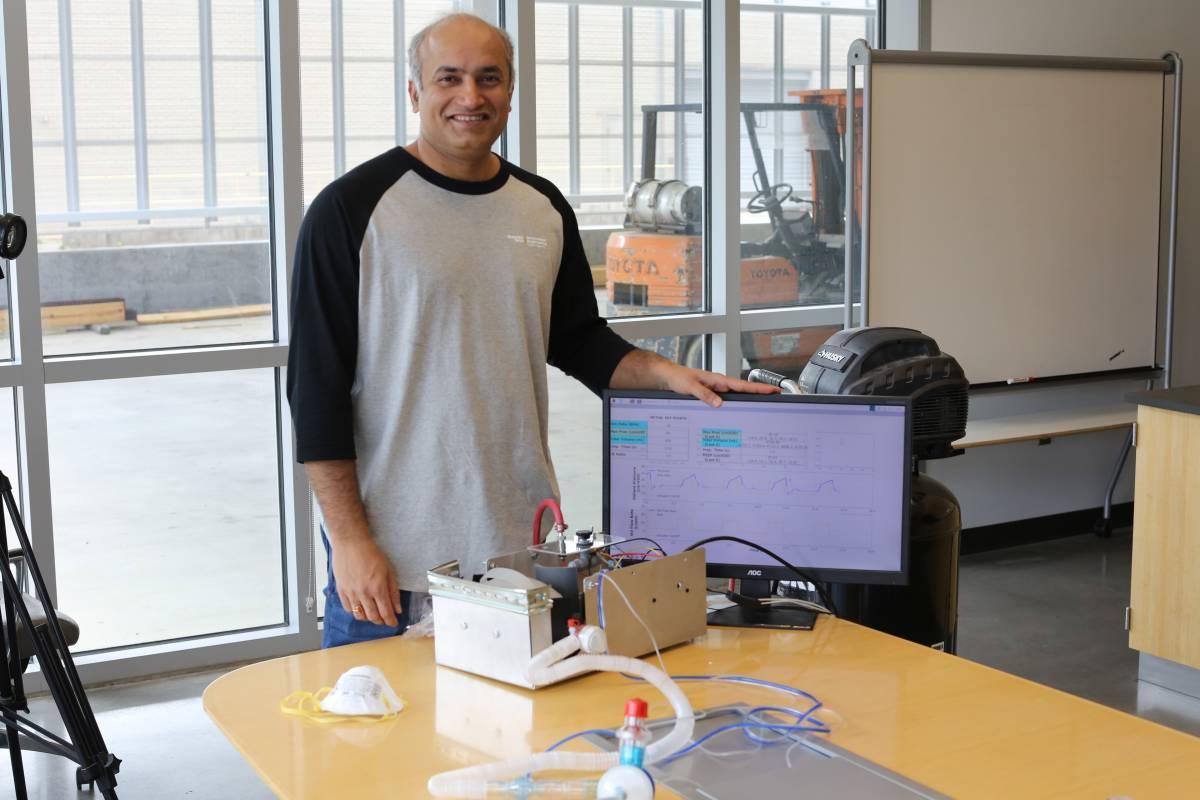

Over the past few months, Devesh Ranjan, who holds the J. Erskin Love Jr. professorship in the School of Mechanical Engineering, and his team of researchers have created a low-cost ventilator with parts that can be sourced in most any country. Kumuda Ranjan, an Atlanta-based physician and wife of Devesh, helped with the development of the ventilator as well.

“We looked at the worldwide data and the global pandemic in terms of how people are facing this ventilator shortage,” said Kumuda. “Devesh asked for my input and together we came up with a solution that includes a patient monitoring system. We also worked alongside Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta doctors to ensure the correct functionality.”

With the design in place, Devesh is focused on manufacturing and how the ventilator can be rolled out to other countries that lack medical infrastructure. And he started with his home country of India, reaching out to 12 companies who could make the low-cost ventilator. Devesh’s goal is to make sure the technology transfer happens in a way that local companies can make the ventilators on their own with easily sourced and interchangeable parts.

“I’m in discussion with three of the 12 companies I reached out to right now,” said Devesh. “We need to make sure the device can be commercialized in these countries in order to see a real impact. We want to see the devices being used.”

One of the challenges in getting the devices rolled out globally is that countries like India don’t have clear guidelines or a government body like the FDA. Devesh is working closely with Indian Ministry of External Affairs and Indian Consul General in hopes to find a pathway to commercialization. This includes building relationships with manufacturers as well.

“One of the things that Covid-19 has taught us is that you cannot rely on one countries manufacturing power because if that shuts down, it creates a big challenge to getting devices out to the healthcare workers,” said Devesh. “So, I’m a big fan of what you can make locally with things that are already used in other devices.”

Kumuda adds that she sees the low-cost ventilator being used in other countries across the world due to easily available parts that are inexpensive.

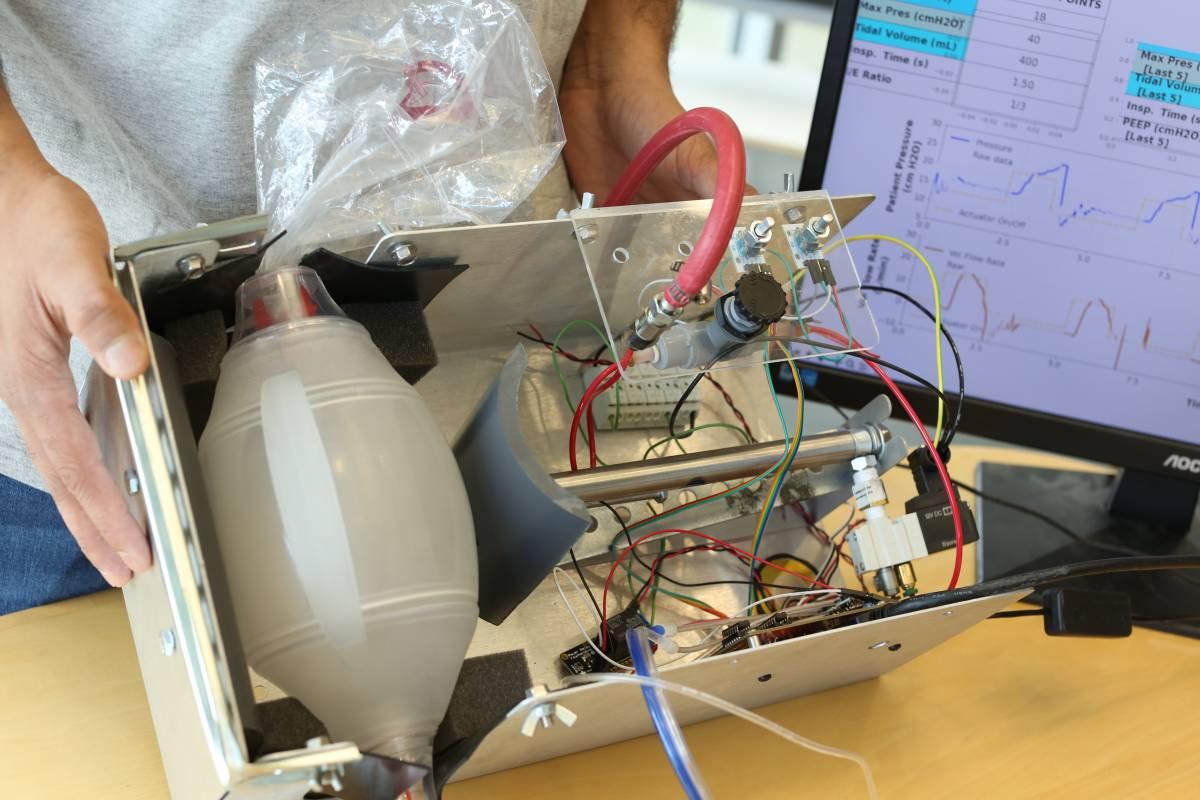

“These ventilators can be assembled anywhere without having to build a unique factory,” said Kumuda. “I feel these ventilators can be used for Covid-19 but also for other treatments in rural areas that lack medical infrastructure. When you look at usability, we need to scale up and get these devices to the remote places that need them.”

According to Devesh, in his state of Bihar, India, 36 percent of people live below the poverty line, and there might be one hospital with 40 to 50 beds for an area the size of Atlanta, presenting a real challenge as Covid-19 cases rise. Regular ventilators are very expensive, but if the low-cost ventilator is able to be deployed at less than $1,000, hospitals can afford to have multiple devices on hand. And when a virus spike happens, the hospitals can be ready.

In India, there are a few large companies that can provide parts, including patient tubing, bag valve masks and the control panel that monitors the patient’s respiratory vitals. Other countries in places like South America have trouble sourcing the control panel, but Devesh is working with a company in Peru to help them manufacture the circuit boards or even ship them there from Georgia Tech.

“Covid-19 numbers are also going up in Brazil, so we are looking to see what they will need to create the low-cost ventilator,” said Devesh. “The idea is to get the royalty-free design of the ventilators to these countries asap, and then let them build it on their own so it’s sustainable and scalable.”

In Africa, countries like Nigeria and Ghana are also looking to adopt the low-cost ventilator. Nigeria could feasibly use its KIA Motors supply chain as an assembly line. Ghana is looking at the product and trying to figure out what they need to do with their local group to get manufacturing started. The interest came from a recent talk Devesh gave at the World Economic Forum (WEF), where they discussed putting Devesh’s design on their file sharing platform so manufacturers would be able to download his design. While at WEF, Devesh also connected to the Lighthouse Network Group, a group of manufacturers trying to respond to the pandemic and very open to creating solutions by working with industry and universities.

“The World Economic Forum is the best way to push out the ventilator design to African countries because the forum has many connections with companies that are trying to build and work with a wide variety of suppliers there,” said Devesh. “The Forum enables us to make things happen a lot faster.”

Devesh is doing his best to fast track the manufacturing of the ventilators.

“For Covid-19, the challenge wasn’t to make the best ventilator, but rather it was to make something that could be adopted the by hospital systems that is safe and able to be manufactured in large numbers very quickly,” said Devesh. “And you want to make sure mass manufacturing is done correctly.”

From the start of the pandemic, Devesh and Kumuda saw the challenges that the US healthcare system was experiencing and knew it would be even more challenging for India where poor hygiene and high density populations create a faster spread of infection.

“It really hit me once we started working on this project on a daily basis with frequent team calls to learn what was going on at Emory Hospital in Atlanta,” said Devesh. “It was our partnership with the hospitals here that made us aware of what was going on in a real system and what we needed to do to address the challenges that other countries are up against.”

Developing nations will continue to need access to low-cost healthcare devices, and Devesh and his team are already thinking about what to create next.

More on Devesh’s group:

Gokul Pathikonda, a postdoctoral fellow in Ranjan’s lab led the engineering development of the device. In addition to Ranjan and Pathikonda, the multidisciplinary research team includes Stephen Johnston, Dan Fries, Cameron Ahmad, Benjamin Musci, Chang Hyeon Lim and Prasoon Suchandra, graduate students in the School of Mechanical Engineering; Kyle Azevedo, a research engineer with the Georgia Tech Research Institute; Prithayan Barua, a graduate student in the College of Computing working with Prof. Vivek Sarkar; Chris Ballance, a research engineer in the School of Aerospace Engineering; and Richard Bedell, Manager of Equipment Engineering and Support Services in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry. They are also being assisted by Kyle French and Biye Wang at the Electronics Shop in the School of Mechanical Engineering.