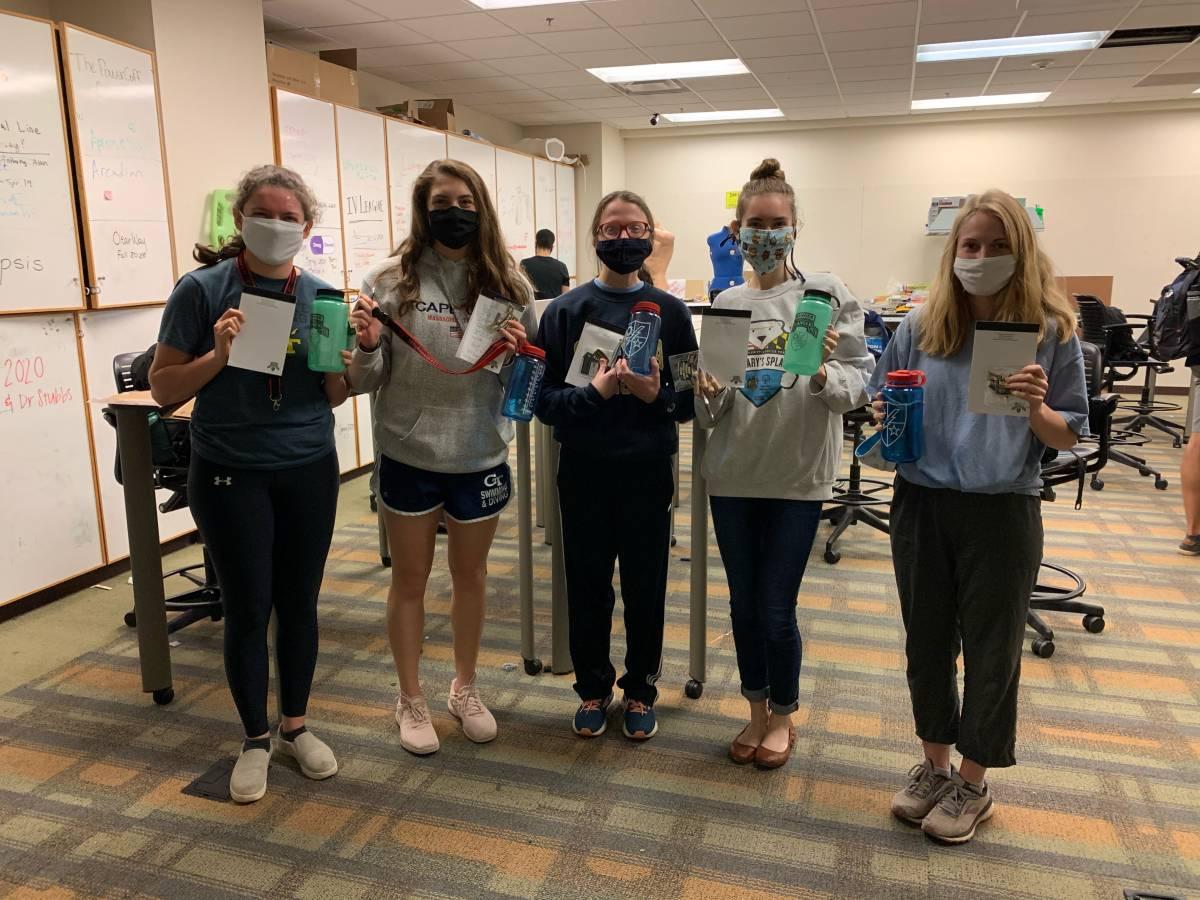

Five biomedical engineering students spent the summer working with the National Security Innovation Network

Veterans of the United States Military characterize traumatic brain injury (TBI) as an “invisible wound of war.” A large explosion from an improvised explosive device (IED) can cause a variety of head traumas – besides the damaging effect it has on the brain, soldiers will oftentimes injure their heads through violent impact with other objects inside a vehicle. TBI research began to pick up traction in the biomedical community in the early 2000’s and is now a large topic of concern. The effects of repetitive, low-level blasts, such as those associated with the mortar and other concussive weapon systems, have gone relatively unexamined in the military sector, according to the US Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs.

Ranger mortarmen – or indirect fire infantrymen – can be expected to fire 100 to 200 mortar rounds a day during training and at least 200 rounds a day, every day for four months, during their deployment – a significant number of exposures. A single mortar blast will not cause as much damage as a high-impact explosion, but as the effects of these blasts add up over time, soldiers begin to report TBI symptoms.

A group of five students from the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University, Project Halo, collaborated with the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN) this summer to find ways to test the effects of blast exposure and its correlation to TBI. They have transitioned this internship into their BME Capstone project.

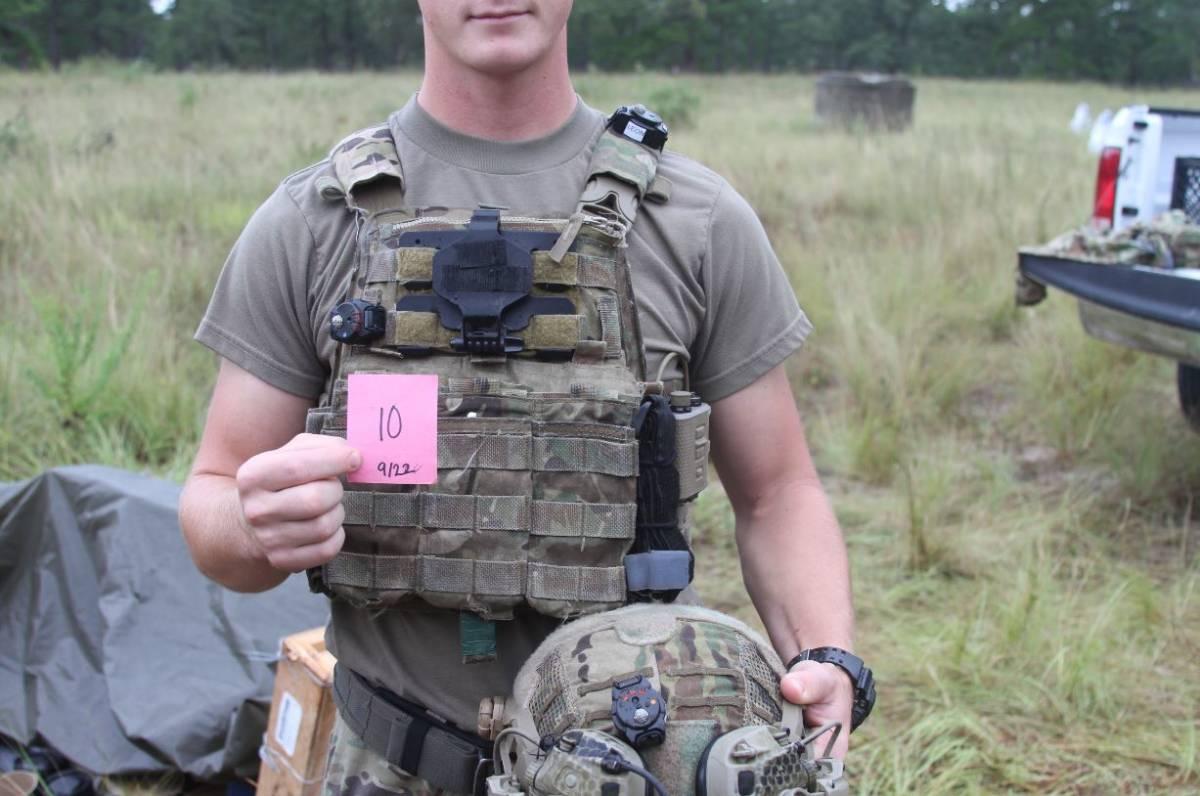

The team partnered up with the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Benning Military Base to gather data about low-level blast exposure. The Army Rangers community is at a significantly higher risk for TBI due to the increased frequency of training and deployments they experience in comparison to those who are not Special Forces.

“The problem that our project sponsors presented to us was that during training and deployment, the rangers were reporting symptoms like headaches, dizziness, ringing in their ears, and in some of the severe cases they felt nauseous and would vomit after a long day of firing mortars,” said Project Halo’s Jessica Nicholson, a fifth-year student.

“The brain is already really confusing, especially with understanding how a single blast affects function, but understanding how over a span of 10 years a small blast can continually damage the brain is a really novel space in research and has not been significantly looked at" -- Julia Woodall

The constant exposure to low level blasts becomes an occupational hazard for the Rangers, especially the mortarmen, who can fire these larger weapons systems for five to 10 years if they have a long career.

“The brain is already really confusing, especially with understanding how a single blast affects function, but understanding how over a span of 10 years a small blast can continually damage the brain is a really novel space in research and has not been significantly looked at,” said Project Halo’s Julia Woodall, a fifth-year student.

Nicholson and Woodall, along with fifth-years Jordyn Sak, Brady Bove, and Grace Trimpe, traveled to Fort Benning for a week in September to measure the physiological effects of low-level blasts from mortars and other weapons systems on the Rangers. They used blast gauges to measure the blast overpressure, pupilometers to measure pupillary light reflex in the soldiers, and symptom questionnaires before and after training.

The team made a major contribution to the NSIN’s goal of defense innovation, according to Dana Sanford, NSIN X-Force program manager.

“Jessica, Grace, Brady, Julia and Jordyn were professional, committed, enthusiastic, and passionate about their work,” said Sanford. “In addition to providing excellent research on traumatic brain injuries for the 3/75th Ranger Regiment, they also were wonderful contributors and leaders for our X-Force Fellowship. They routinely went above and beyond what we asked to help create a culture of innovative National Security problem solvers.”

The team plans to use its research on blast exposure to prototype a blast attenuator, which fits over the muzzle of a mortar. “The blast attenuator will mitigate the blast overpressure exposure of the gunner and assistant gunner in a ducking position directly beside the mortar while the mortar fires,” said Nicholson. The team will use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling to test various prototypes and assess the alleviation of blast exposure on soldiers manning the mortar.

Outside of using its research for a Capstone prototype the team is interested in publishing its findings to motivate more research about blast exposure effects and inform others who are interested in creating solutions to this understudied issue.