Mathematicians and engineers from Georgia Tech and Carnegie Mellon discuss how network and game theories provide a different way to control the spread of infectious disease

Contact tracing apps have become a crucial way for people to keep themselves and others safe during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, contact tracing is often a reactive rather than proactive way of monitoring the spread of disease. An alternative digital tool is an early warning system that anonymously alerts users as a Covid-infected individual approaches their social interaction circles – simply put, a Covid radar system.

In an event co-hosted by the College of Engineering and the College of Sciences, Georgia Tech faculty members Matt Baker and Shannon Yee invited Po-Shen Loh, a professor of mathematics at Carnegie Mellon University, to speak about the innovative radar approach, as well as NOVID, an app pioneered by Loh and his team

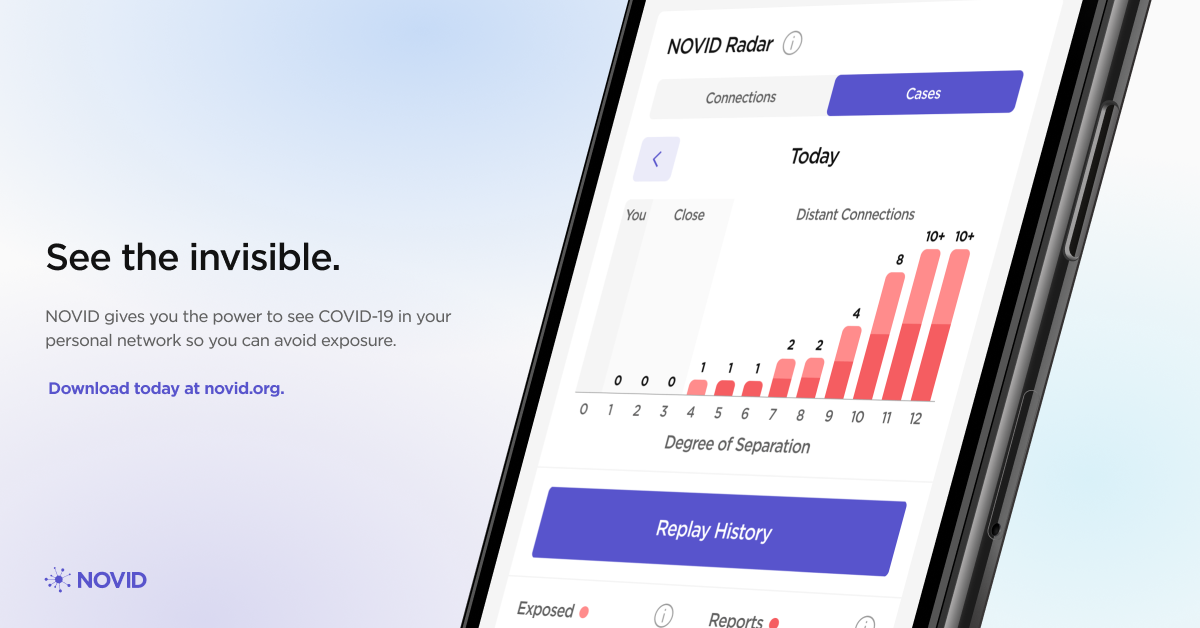

In March 2020, Loh began the theoretical plans for the NOVID app. He wanted to find a way to apply his scholarly work in times of national emergency, which led him to examine mainstream contact tracing apps that emerged at the beginning of the pandemic. Using his expertise in network theory – the study of the way elements in a network interact – Loh and his team wanted to create an app that would empower people with information, including when to take extra precautions to mitigate exposure, such as wearing a more protective mask or avoiding optional social gatherings. To do so, they created what he describes as a Covid radar app that provides users with a self-defense mechanism to avoid infection, showing multiple degrees of separation from infected individuals.

Combining Game and Network Theory

Here is where Loh’s application of game theory comes into play – the team had to find a way to align the user’s natural incentives with downloading the NOVID app and did so by offering opportunities for the user to be proactive and protect themselves. Loh started with a question – how a new methodology focused on game theory and networks could affect contact tracing apps – and ended up with an app that has seen more than 100,000 users.

Some contact tracing apps use smartphones’ ability to connect to inform users if they have been physically near an infected individual, measuring distance in terms of feet or miles, but Loh felt their approach needed a methodological shift. They went one level of abstraction up, measuring distance in terms of sustained physical relationships – mapping those smartphone interactions onto a network and measuring degrees of separation from infected individuals by network distance. His idea is extrapolated from network theory, where each node in the system is a person, and when two people spend a significant amount of time physically near each other, it forms a connection between those two nodes. The app can then measure the distance between a user and infection by measuring how many steps away on the network the user is from an infected individual.

“If you flip the way you're measuring distances, you flip the paradigm from focusing on immediate physical distances and times and changing that into one layer of abstraction up, which is the network graph-theoretic distance,” -- Dr. Po-Shen Loh

A Shift in Approach

While most contact tracing apps notify a user to quarantine after physical exposures, Loh’s app gives users visual representation of how far away in terms of degrees of separation they are from an infected individual, and allows the user to become aware of their interactions and environment to make more proactive decisions.

During the event, Loh outlined three main problems he found in mainstream contact tracing apps that create a significant barrier to their success. One such problem is the threshold that most contact tracing apps are calibrated to: a six-foot distance from an infected person for a period of 15 minutes, measured via Bluetooth connections with other smartphones. The likelihood that the user has actually contracted the disease in the above situation is about 6%, according to findings in a UK study about contact tracing, and many users will not voluntarily self-quarantine for such a low chance of infection, or even decide to participate in contact tracing at all. To solve the problem of mistrust in these apps’ recommendation to quarantine, NOVID does not tell users to do so, but instead educates the user on how far away they are in the network from infection and recommends simple, temporary lifestyle changes, such as spending time with friends outside, not going out to eat, and other safety methods.

“Traditional contact tracing relies to a large extent on altruism, but the NOVID app flips the incentives around and relies on users’ desire to protect themselves,” said Baker. “It’s a marvelous idea and the potential applications are not limited to Covid-19, or even to epidemiology.”

The NOVID team continues to work with researchers and epidemiologists to analyze and improve the app, and they plan to release a new update that allows users to input vaccination status in a few weeks.

“I’m really intrigued by the whole project and interested to see where this app will go,” said Yee. “I chose to teach in-person this semester, and NOVID provides me peace of mind when I go home at night regarding the prolonged interactions I may have on campus. It’s great to have this app in the Georgia Tech toolkit to help stop the spread of Covid-19 in our community.”