Iris Tien’s method reduces the possible locations for sensors by nearly 99% and accounts for flood risk, population vulnerability, and more.

An aerial view of the Tybee Island marina in Chatham County, Georgia.

As climate change leads to rising sea levels and more powerful storms, coastal communities increasingly are turning to networks of sensors to track water levels. The sensors — which are progressively getting cheaper and more capable — can help officials anticipate flood risks and respond in emergencies.

A tool developed by Georgia Tech researchers can help make the most of those networks, pinpointing the ideal locations for water level sensors to maximize the real-time data available to emergency managers.

In a test case in Chatham County, Georgia, the approach developed by civil engineer Iris Tien reduced 29,000 potential sensor locations to just 381. The idea, then, is that officials can use their local expertise and historical knowledge to pick where to install sensors among those spots.

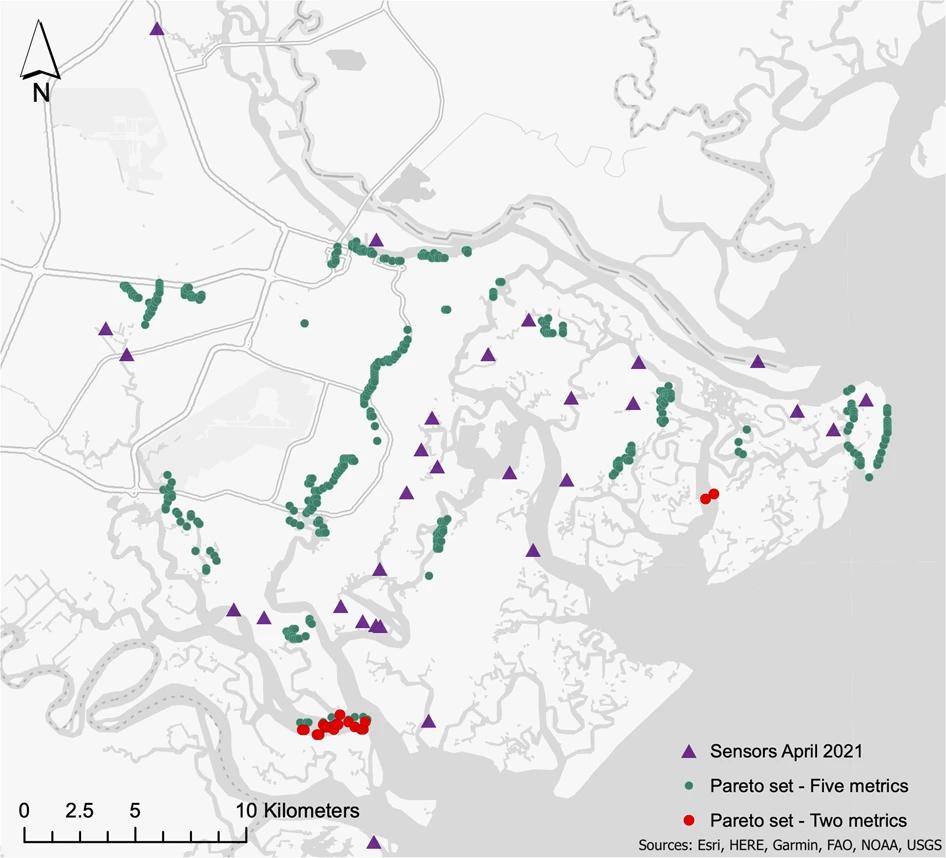

This map of Chatham County, Georgia, shows potential locations for new water-level sensors. The red dots indicate locations identified using only the two traditional metrics: filling gaps in the network and reducing uncertainty caused by the limited reach of the network. The green dots show potential locations using Iris Tien's optimization tool that also accounts for additional factors like likelihood of flooding, exposure risk for critical infrastructure, and social vulnerability metrics. (Image Courtesy: Iris Tien)

“We wanted to make sure to integrate that local expertise,” said Tien, Williams Family Associate Professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “Something that I think is often missing in research is that there is specific local knowledge that can add value to the project and the solutions. That was part of our cooperative process: These are people who’ve seen flooding in the community and who know where sensors might be beneficial.”

Tien has just published details of the tool in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment with Ph.D. student Jorge-Mario Lozano and intern Akhil Chavan. Tien stressed the approach would work in any coastal community. The code and instructions are freely available as part of their study.

Chatham County Emergency Management, the city of Savannah, and Georgia Tech have been collaborating for years on a low-cost sea-level sensors project to provide real-time information for emergency planning and response. As the network of sensors has expanded, the team chose locations to fill gaps in data and to try to reduce the uncertainty caused by the limited reach of the network. But they wondered if there was a more effective way.

“We’ve been placing these sensors in an ad hoc manner based on where we think might be good,” Tien said. “In our discussions, we started thinking that maybe there’s a way we can make this a bit more quantitative, more rigorous, and include specific factors in making those decisions.”

As the team dug into research on sensor network placement, they found assessments usually only accounted for the same gap-filling and uncertainty issues that the sea-level sensors team already had been considering.

Tien’s tool adds other critical components to the calculus: the likelihood of flooding in different areas based on federal flood data; the potential exposure of critical infrastructure like hospitals, schools, power stations and more; and social vulnerability metrics that aim to account for populations who struggle the most when impacted by flooding.

“The overarching goal of this project is really three words: increasing community resilience. That leads us to the question of what might help us increase community resilience,” Tien said. “A lot of these events disproportionately affect more vulnerable populations. So it’s important that we include that in the analysis to address historical underinvestment or historically marginalized communities that haven’t received the attention they need to be more resilient to these types of events.”

In Chatham County, emergency planners have created a Damage Assessment Priority Index that combines socioeconomic and social vulnerability indicators to help prioritize response efforts. It looks at households below the poverty level, unemployed populations, the number of renter-occupied homes in a neighborhood, multi-unit housing and mobile homes, and more.

Tien’s team used that index in their assessment alongside the kinds of critical facilities Chatham officials identified. In other communities, the variables might be slightly different, Tien said — maybe different critical infrastructure or different priority populations — but the tool is easily adjusted to account for local needs. And it doesn’t require massive computing power; it can be run on a desktop computer.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

We live in a world where there are limited resources. There isn't unlimited funding to buy sensors, install them, and maintain them. We want to provide methods to make smarter, more effective decisions.

IRIS TIEN

Williams Family Associate Professor

“We live in a world where there are limited resources. There isn't unlimited funding to buy sensors, install them, and maintain them. We want to provide methods to make smarter, more effective decisions,” Tien said. “This approach enables planners to use resources more effectively to monitor the things they really care about and help build resilience for those particular locations or populations.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

With Recent Funding, Sea Level Sensor Project in Savannah Moves into New Phase

Now in its fourth year, the sea sensor project is slated to receive $5 million from Congress to launch the Coastal Equity and Resilience Hub and expand the network of sensors to blanket Georgia’s 11-county coastal region.

The Rising Tides

Georgia Tech scientists and engineers have been working with the people of flood-vulnerable Savannah and Chatham County to improve emergency response and preparedness in a coastal region whose past, present, and future are inextricably linked to water.

About the Research

CITATION: Tien, I., Lozano, JM. & Chavan, A. Locating real-time water level sensors in coastal communities to assess flood risk by optimizing across multiple objectives. Commun Earth Environ 4, 96 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00761-1