With a flexible, no-equipment-needed platform, ChBE researchers are creating a new way to test for disease at home or anywhere medical resources are limited.

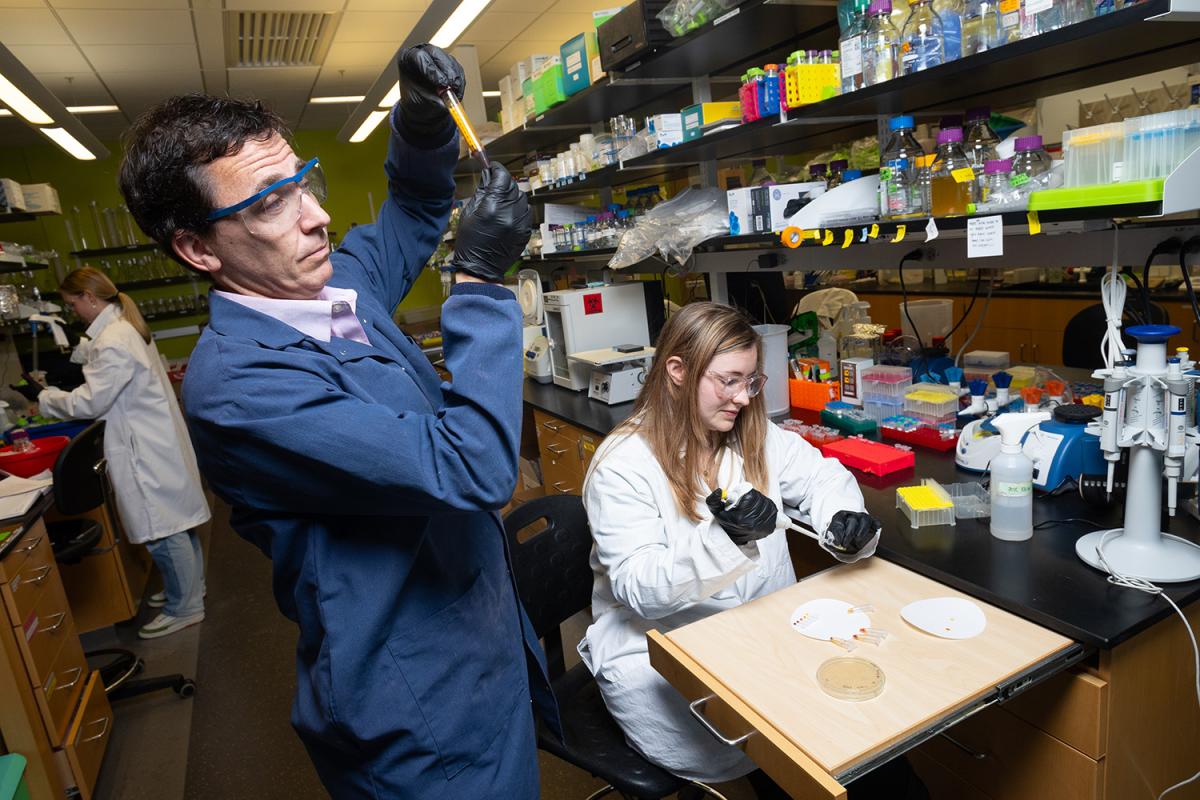

A new protein biosensor platform developed Mark Styczynski's lab requires no expensive lab equipment and is easily adapted to detect many different kinds of disease biomarkers. The test produces a clearly visible color output in colors that vary depending on the concentration of protein detected. Designed for point-of-care use — at home or in places with limited medical resources — the platform also can be modified to produce a more detailed output for deeper analysis in a lab. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Chemical and biomolecular engineers at Georgia Tech have developed a plug-and-play platform for detecting protein biomarkers of disease that’s simple, flexible, and easy to use without costly lab equipment.

Their work could unlock a new wave of at-home testing options and provide new diagnostic capabilities in parts of the world where medical resources are scarce.

The testing platform fills a gap in using cell-free synthetic biology for disease detection. Existing cell-free tools have proven effective at measuring DNA, RNA, and other small molecules, but not proteins. That’s an important advance because proteins in viruses or bacteria tend to change less than the DNA or RNA sequences that encode those proteins. They’re also easier to detect since they can be found on the outside of cell walls or free-floating in biofluids.

“Diagnosing disease and democratizing medical care by putting it into the public's hands has great potential. You can have a big impact on a lot of people,” said Mark Styczynski, William R. McLain Endowed Professor in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

“I think about that a lot in terms of the developing world, but also there's a lot of healthcare inequality even in the United States. Studies have shown your ZIP code can determine your life expectancy. You can think about people in sub-Saharan Africa or people in rural Appalachia all benefiting. They’re among those who need more access to low-cost tools.”

Styczynski and a group of researchers led by former Ph.D. student Megan McSweeney presented their test in late February in the journal Science Advances.

They described it as a modular cell-free protein biosensor platform. Cell-free, meaning the team uses the kind of machinery found in cells but engineer it in the lab rather than in cells. And modular because they showed their platform can easily be adapted to detect a variety of proteins.

The tool can produce a visual result akin to a swimming pool pH test strip, or it can provide more precise information for use in a clinical or research lab.

“Flexibility was one of the things we wanted to focus on most, because we know just how powerful that feature is to synthetic biologists and engineers making these biosensors, and specifically for proteins,” said McSweeney, first author of the study and now a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University. “The level of flexibility that we achieved here is quite astounding.”

In their paper, McSweeney and the researchers successfully detected a biomarker for malnutrition and a protein from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. The proteins they targeted in those two cases were vastly different in size, demonstrating a wide range of potential uses.

Experiments showed the test worked in pooled samples of human blood serum and saliva. McSweeney said they expect the sensing platform would work across many other biofluids.

“It can take years of development and potentially millions of dollars to make one lateral flow test, which is what your at-home Covid test is,” Styczynski said. That’s why their platform is so powerful: changing the target is as simple as changing out a few of the ingredients, without needing to optimize the testing protocol or reengineer all the parts of the test.

The team's modular cell-free protein biosensor platform produces a simple color output based on the amount of protein detected in a sample. That makes it easy for any user, without specialized training, to read the results of a test at home or in areas with limited access to medical resources. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

“We can easily swap these out, and then we don't have to worry about all that other crazy, multimillion dollar development. It just works,” he said.

How? The researchers use RNA polymerases, which can turn genes on and off. They attach two pieces of those to what are essentially very simple antibodies. Those antibodies are designed to find and bind with a particular protein. When they do, the RNA polymerase pieces that are now next to each other will connect.

When they “click” together, the RNA polymerase activates an enzyme that causes a dye molecule to change color. In the simplest version of the test, finding the target protein results in a range of colors — from yellow to orange to red to deep purple — depending on how much protein is present.

For a lab version of the test, the results could be a fluorescent output that could be plugged into lab equipment for more detailed analysis.

“We wanted to also frame this technology as something that's versatile enough to be used by people who have advanced lab equipment and resources,” McSweeney said. “Our platform is flexible enough, I think, to cater to those people's needs, potentially increasing their throughput, their consistency, and their quality of data.”

The test’s modularity opens the possibility of use in disaster, first-response, and military settings, too. Styczynski suggested the platform could become a field kit for those scenarios, where technicians with a bit of training could easily mix the elements of the test on the fly to detect a variety of pathogens or biomarkers. The kit would have a number of raw materials and a set of “recipes.”

Along with former Georgia Tech Ph.D. student Monica McNerney, McSweeney and Styczynski have applied for a patent on their approach. The research team also included Ph.D. students Alexandra Patterson and Kathryn Loeffler, undergrad researcher Regina Cuella Lelo de Larrea, and Garry Betty/V Foundation Chair and Professor Ravi Kane.

The researchers continue to develop the tool. They’re working to detect even lower levels of target proteins and make the test platform more user-friendly. For example, their preliminary work showed it can withstand the process of lyophilization, which eliminates the need for special storage or refrigeration. But they said more work is needed to ensure the test would be shelf-stable in longer-term, real-world conditions.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

About the Research

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant Nos. R01EB034301, R01EB022592, and P01AI165077, and the National Science Foundation, grant No. DGE-2039655NSF. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding agency.

Citation: McSweeney M, Patterson A, Loeffler K, Lelo de Larrea R, et al. A modular cell-free protein biosensor platform using split T7 RNA polymerase. Sci. Adv. 11, eado6280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado6280

Preeminence in Research

Related Content

3 New NSF Projects Will Use Biological Principles to Address Societal Challenges

ChBE researchers will lead three of 12 projects awarded under “rules of life” grant program, working to boost crop production, secure synthetic biology, and develop “protocells” for sensing.

New Test Detects Life-Threatening Zinc Deficiency

With a quick fingertip prick, an experimental malnutrition test made with bacterial innards could help expose widespread zinc deficiencies that kill thousands every year.