Using a simple setup and advanced processing, engineers can reliably detect physiological signals such as temperature, breathing, and pulse. The technology could open new possibilities for early disease detection.

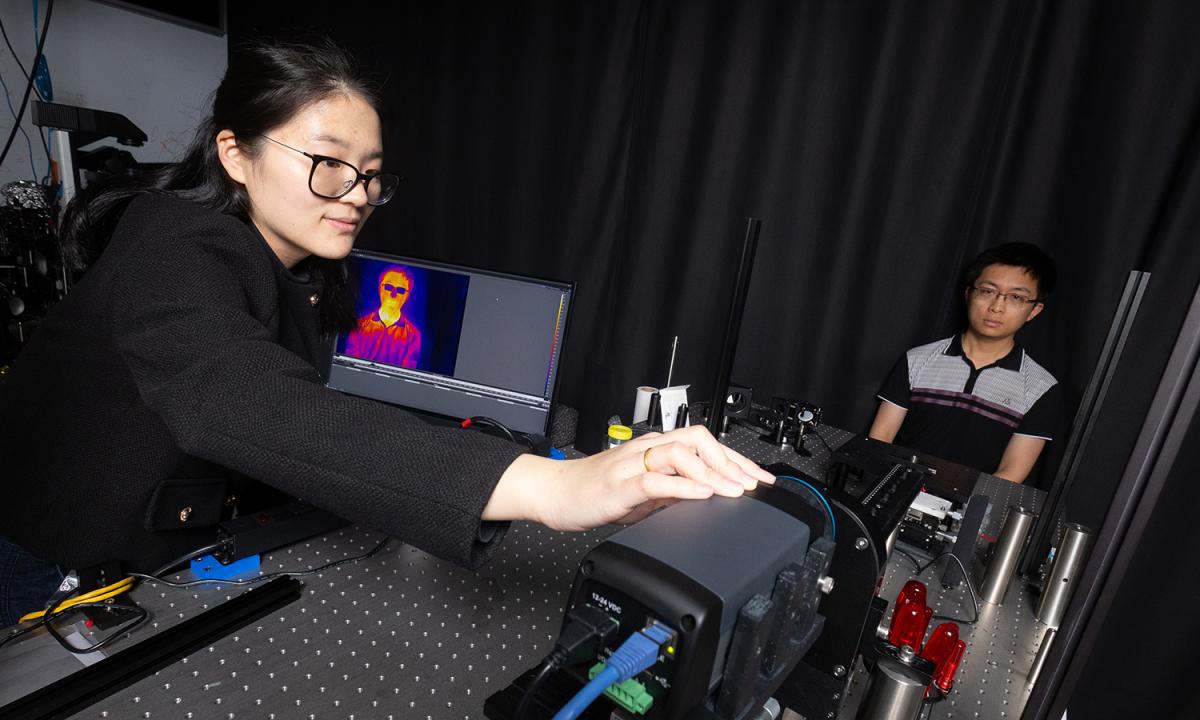

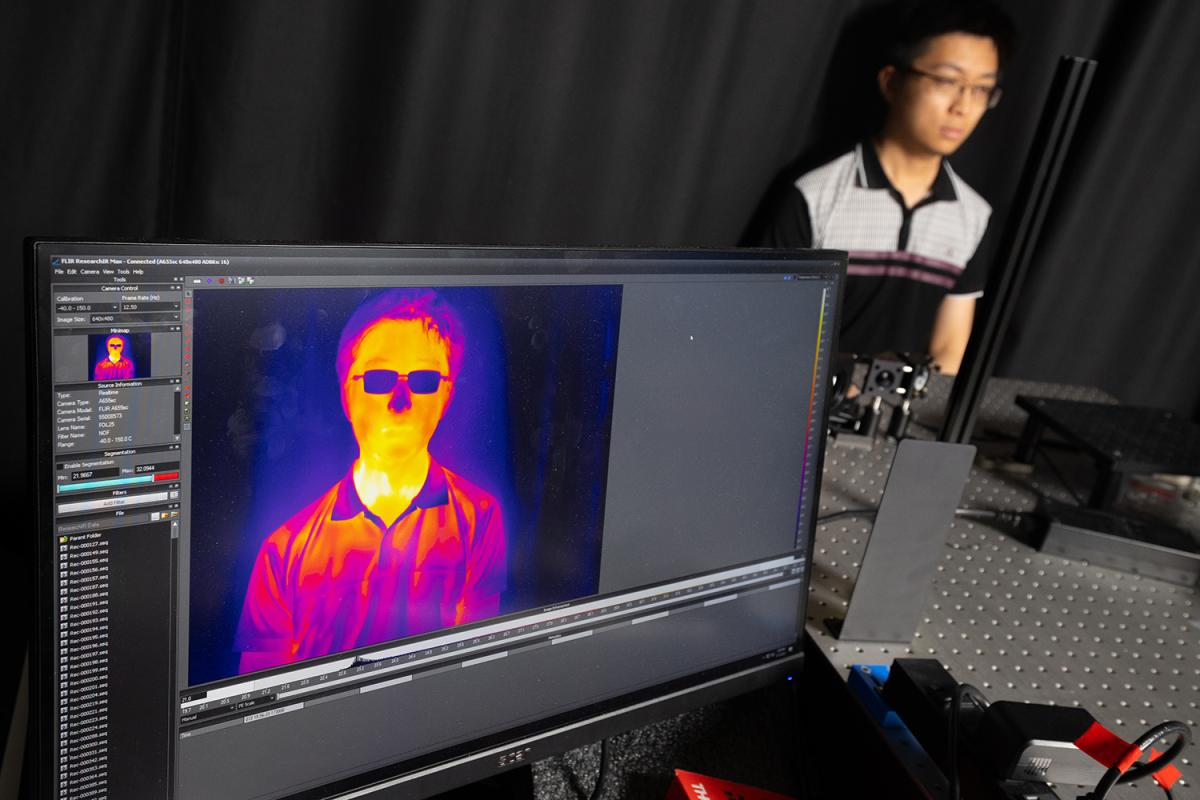

Postdoctoral scholar Dingding Han adjusts a thermal camera capturing an image of Ph.D. student Corey Zheng. Using an advanced processing technique on the raw thermal image, Han, Zheng, and their collaborators can accurately measure body temperature, heart rate, and respiration rate. Their noncontact technology could open new possibilities for vital sign monitoring and early disease detection. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Biomedical engineers at Georgia Tech have developed a system for collecting and processing thermal images that allows for reliable, detailed measurement of vital signs such as respiration and heart rate or body temperature.

Their monitoring approach is passive and requires no contact. The system could one day lead to early detection for cancer or other diseases by flagging subtle changes in body tissues.

The researchers have overcome the spectral ambiguity inherent in conventional thermal imaging, sharpening the texture and detail they can extract from images and removing the effects of heat from the environment surrounding a subject.

They published details of their work March 19 in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science.

“This could be a cornerstone for future broad biomedical diagnosis,” said Dingding Han, lead author on the study and a postdoctoral scholar in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “With this phasor thermographic technology, we can enhance the accuracy and efficiency of thermal imaging to detect abnormalities. Phasor thermography has the capability of getting material segmentation, which is not possible with only pure thermal imaging.”

What drives the improvement in Han’s system is its ability to eliminate the “fuzziness” of typical thermal images. Usually, they don’t sharply differentiate between subtle temperature variations, and heat in the environment can make the images too noisy for precise measurement of physiological signals.

In the study, the researchers showed they were able to precisely measure heart rate, respiration rate, and body temperature from multiple parts of the body. They reported the tool effectively differentiated vital signs in scenes with multiple people. It also accurately captured variations in respiration rate before and after exercise.

Han and the research team used a series of filters to capture 10 images of different parts of the infrared spectrum — specifically long-wavelength infrared. This part of the electromagnetic spectrum is beyond the light visible with the human eye. Long-wavelength infrared is the area where thermal radiation is detected.

With those 10 images, they deployed a powerful mathematical tool borrowed from signal processing called thermal phasor analysis. Their algorithms resolved textures in three dimensions smaller than a millimeter. That detail enabled them to effectively distinguish fine thermal variations — for example, facial skin, thick hair near the scalp, thinner hair of eyebrows, and even metal rims of eyeglasses on a human subject.

What’s more, Han said, the system uses common equipment, making it powerfully adaptable.

“We used a thermal camera and the filters to get the hyperspectral image data. So, it’s scalable,” she said. “You could integrate this setup into virtually any thermal imaging platform.”

As a result, Han said the system could easily integrate into hospital or other healthcare settings. She’s working on a grant to further develop her prototype system and work with doctors to apply it specifically to spotting breast cancer tumors.

The image immediately above shows the additional detail and contours of temperature and shirt material in a processed phasor thermographic image. At top, the computer shows a raw image from the thermal camera. (Photo: Candler Hobbs; Image Courtesy: Dingding Han)

“Thermography could give us an advantage in early detection, because it could noninvasively detect abnormal cell activity that indicates early cancer,” Han said. “For example, tumor cells need more oxygen to reproduce, so their temperature will be a little bit higher than normal tissue. With this phasor thermography approach, we could spot that.”

Han developed the system while working in Shu Jia’s lab in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering. Jia is the senior author on the study describing the system; other coauthors are Ph.D. students Corey Zheng and Zhi Ling.

“This can be the first step for the next generation of biomedical thermography for early detection and diagnosis of cancer. That’s what I’m working toward,” Han said. “It’s the first prototype with an ultimate goal of evolving the next versions and making it easier to use in hospitals and clinics.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

About the Research

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant No. R35GM124846 and the National Science Foundation, grant No. BIO2145235. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding agency.

Citation: Han D, Zheng C, Ling Z, and Jia S. Hyperspectral phasor thermography. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2025;6:102501. doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrp.2025.102501

Preeminence in Research

Related Content

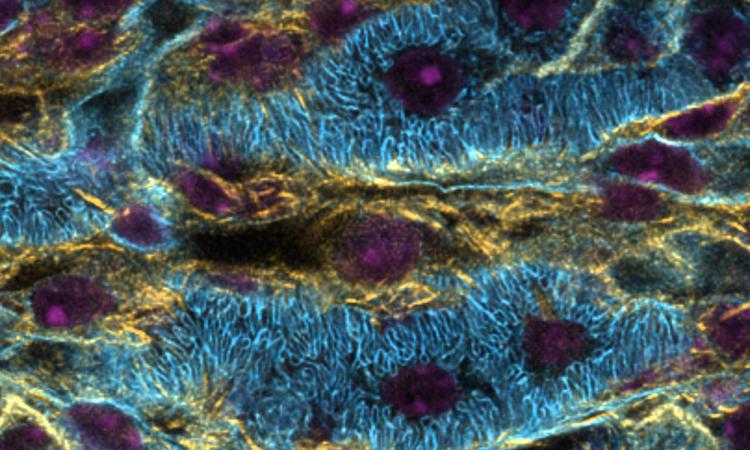

Designing the Future of Image Restoration in Fluorescence Microscopy

New technology can transform the way scientists view and interpret microscopic images.

Reimagining At-Home Breast Cancer Screening

Bioengineering Ph.D. student Gianna Slusher has patented a device that uses a smartphone or tablet and thermal imaging to scan for potential tumors.