The competition asks students to use engineering fundamentals to create solutions that improve the experience for all students in the College community.

Amid the scramble of studying for spring finals and ironing out details for summer work or vacation plans, international students often have another looming question: what to do with all their stuff over the summer.

Enter a group of engineering students who aim to connect those students with others in the Georgia Tech community who have some space and are willing to store those belongings — while charging less than traditional self-storage options.

Their peer-to-peer storage platform took top prize this spring at the 2025 edition of the FAIR Tech innovation competition hosted by the College of Engineering. The goal is to inspire students to use engineering principles to develop ideas that improve the experience for everyone on campus. The top three teams win cash prizes.

“This competition is the validation we needed to know that this is a problem space that needs to be addressed and that our solution addresses the needs of the student body,” said Ishita Raghuvanshi, a fourth-year biomedical engineering student.

Second place went to a navigation app to help people with mobility impairments more safely and easily get around campus. Third place was an online platform to help students find free food around campus, with special priority for lower-income students who often need food assistance.

In addition to cash prizes, the three finalists also received $1,000 to prototype and pilot their innovations.

First Place: Peer-to-Peer Storage

For the team behind the winning idea, OneByFour, the idea for connecting students with affordable summer storage was borne out of experience.

“We have a lot of friends who are international students and have seen first-hand how much students struggle to juggle finding affordable facilities, transporting their items, and focusing on their finals,” said team member Gayatri Kumar, who’s entering her final year of industrial engineering studies. “We wanted to focus on an issue that affects a large population to ensure that our solution helps as many people as possible.”

In talking to and surveying more than 200 students, they found traditional self-storage rates can be higher than a college student’s budget might easily accommodate. And none of the businesses is especially close to campus, meaning more costs for transportation.

Their solution would connect students with belongings they need to store to local students, staff and faculty members, or even alumni with some extra space in a basement, garage, or attic.

The OneByFour team. From left, Ishita Raghuvanshi, Devansh Kaushik, and Gayatri Kumar.

Hosts would make extra money while charging a fraction of typical storage costs for space they’re not using. Students would get a more affordable place to keep their stuff. Hosts also could offer transportation for an extra charge.

The OneByFour platform — created by Kumar, Raghuvanshi, and Devansh Kaushik — includes a secure contracts and payment system to ensure safety, and it would be limited to people connected to Georgia Tech.

The group is running a pilot this summer with four paying customers.

“Through the pilot, we discovered that students are willing to pay around $70 per month — roughly 30% of what they would have paid using traditional storage options — to store their belongings for 4 months,” said Kaushik, who just finished his business degree.

The proceeds from the pilot, along with the cash prize from FAIR Tech, will go back into the platform, he said. Later this summer, the team will start to recruit hosts for the fall to help students who are completing internships or co-ops in other cities.

Second Place: Avoiding Mobility Roadblocks

The students behind NavigateAbility were inspired by the challenges team member Saif Aslam regularly encounters navigating his wheelchair around campus.

“For my first year at Georgia Tech, I had to map out my own wheelchair accessible routes just to survive. It was a long and arduous process of trial and error while avoiding cracks, sidewalk decay, e-scooter littering, etc.,” said the second-year computer science major. “I felt out of place and vulnerable every time I traveled somewhere on campus I hadn’t been before. Anytime there was an impromptu event or study session outside of my ‘safety zone,’ I felt I couldn’t go without risking my safety.”

With fellow computer science students and a pair of biomedical engineers, Aslam created a solution: a Georgia Tech-specific map to help people with mobility issues avoid the problems he routinely encountered. That might be temporary barriers — including weather hazards, crowds, or e-scooters blocking pathways — and semi-permanent issues, such as decaying sidewalks, potholes, and blocked ramps.

The NavigateAbility team. Seated in front, Saif Aslam. Standing, from left, Sneha Vashistha, Hannah Koppel, Kripa Kannan, Diya Kaimal, and Nalini Dutt.

Using crowdsourced data from users who encounter issues and computer vision to identify hazards in submitted photos, the NavigateAbility map delivers in-the-moment route updates customized to what an individual user can handle.

The app is a step above typical map apps from Google and Apple, which don’t account for real-time changes.

This summer, the students are working to bring their prototype map to life, testing it with real users on campus to see how it holds up.

“We are also partnering with campus groups like ABLE Alliance, the Student Government Association, and Georgia Tech Infrastructure & Sustainability to make sure the app stays updated with construction zones, paratransit info, and other accessibility-related data,” said Kripa Kannan, a rising third-year computer science student. “It has been awesome to see how much support we have gotten from both students and administration who believe in this mission.”

Alongside Kannan and Aslam, the NavigateAbility team includes Nalini Dutt, Diya Kaimal, Hannah Koppel, and Sneha Vashistha.

“Through FAIR Tech, I had the amazing opportunity to see our idea turn into a real solution, with guidance and funding from the competition,” said Vashistha, a rising third-year biomedical engineering student. “I’m now more excited than ever to continue working with this team to improve upon our solution and bring it to life.”

Third Place: Finding Free Food

The third finalist in the 2025 competition had to pivot after several months of working on their original idea.

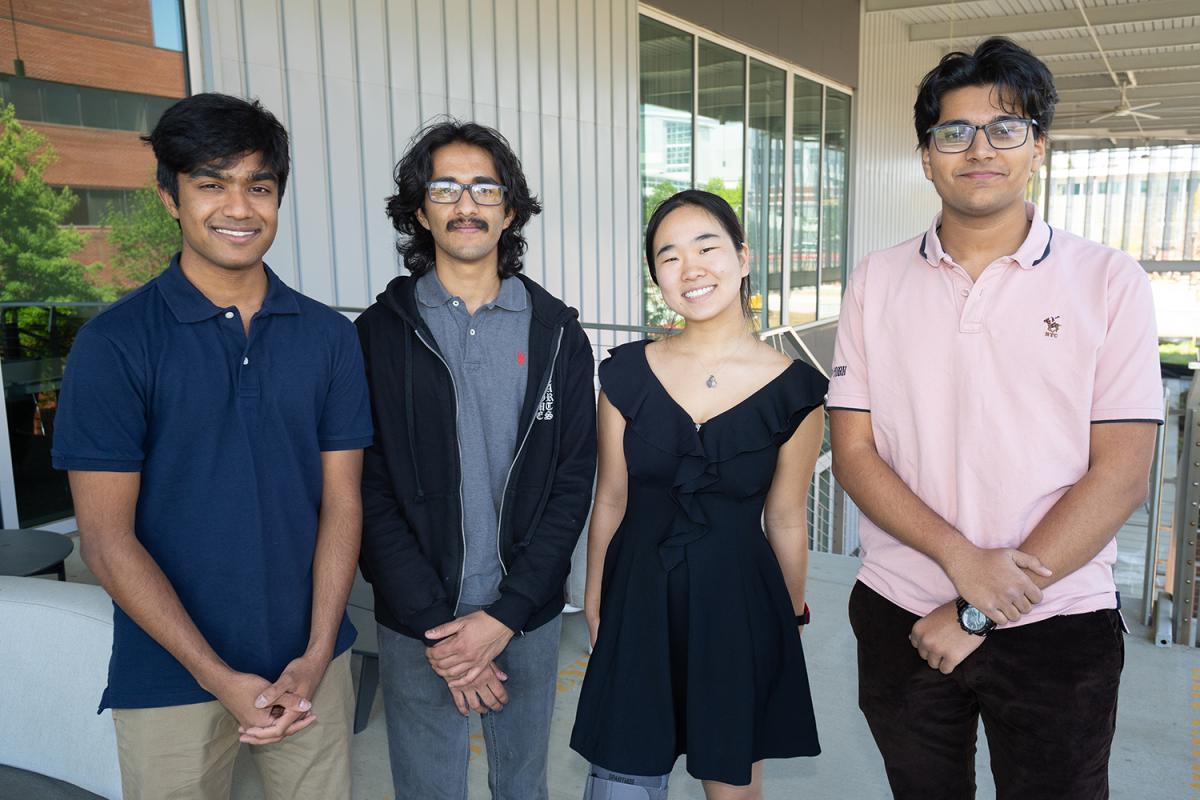

Computer science students Aadit Bansal, Christina Wu, and Jaisen Soundar and mechanical engineer Niyanth Mahesh wanted to provide real-time information to students about food being served at dining halls. They found Georgia Tech Dining already had recognized the issue and started working with an outside company on a solution.

So the team shifted to another food-related problem: helping students who don’t have enough to eat locate free food on campus. Citing studies that have indicated these students are three times more likely to drop out, the team created a new platform they called a one-stop shop for events offering free food.

“Food insecurity on campus is a silent but widespread problem,” Soundar said during the team’s final presentation to judges.

Their site, OpenPlate.org, uses an AI model the team developed to gather data from web calendars, emails advertising events, and several GroupMe groups that share free food opportunities.

The OpenPlate team, from left, Jaisen Soundar, Niyanth Mahesh, Christina Wu, Aadit Bansal.

The team has been working with information technology staff to explore integrating Georgia Tech’s single sign-on system to the site. That would allow them to show students events that are only open to specific majors. It also could allow priority access to food listings for lower income students.

Related Content

International Student Support, Menstrual Products Map Win College’s FAIR Tech Innovation Competition

The competition asks students to use engineering fundamentals to create solutions that promote equity and access in the College community.

The competition asks students to use engineering fundamentals to create solutions that promote equity and access in the College community.

Virtual Reality Learning Tools Win Top Prize in Student Innovation Competition

The competition asks students to use engineering fundamentals to create solutions that promote equity and access in the College community.

The competition asks students to use engineering fundamentals to create solutions that promote equity and access in the College community.