A vaccine delivered to the skin using a microneedle patch gives better protection against the H1N1 influenza virus than a vaccine delivered through subcutaneous or intramuscular injection, researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University have found. Their research is published online in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. Mice given a single H1N1 vaccine through the skin using a coated metal microneedle patch as well as mice vaccinated through subcutaneous injection were 100 percent protected against a lethal flu virus challenge six weeks after vaccination.

Researchers already have found that intramuscular injection is not the most efficient way to deliver vaccines. The muscles have a low concentration of cells needed to relay immune signals and activate a T-cell response, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and MHC class II-expressing cells. The skin, however, contains a rich network of antigen-presenting cells, including macrophages, Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells that activate cytokines and chemokines – immune signaling cells responsible for initiating an immune response.

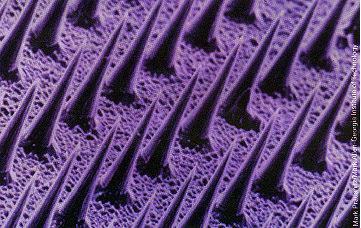

The Emory/Georgia Tech research team previously reported that delivery of seasonal influenza vaccine through the skin using antigen-coated metal microneedle patches or dissolving microneedles elicited strong immune responses that can confer protection at least equal to conventional intramuscular injections. The team has developed dissolving microneedle technology that could be used in easy-to-administer, painless patches. The research team includes Dimitrios Koutsonanos, MD, Ioanna Skountzou, MD, PhD, Richard Compans, PhD, Maria del Pilar Martin, PhD, and Joshy Jacob, PhD, from Emory, and Georgia Tech bioengineers Mark Prausnitz, PhD, and Vladimir Zarnitsyn, PhD.

"Microneedle delivery also offers other logistical advantages that make this method attractive for influenza vaccination, such as inexpensive manufacturing, small size for easy storage and distribution, and simple administration that might enable self-vaccination to increase patient coverage," said Prausnitz.