Georgia Tech plays a starring role in NASA’s STARI mission to determine if telescope technology that studies exoplanets can be implemented in briefcase-sized spacecraft.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

A new NASA-funded project will have Georgia Tech aerospace engineers developing new technology to one day study planets outside our solar system.

It's a $10 million joint mission led by the University of Michigan called STARI — STarlight Acquisition and Reflection toward Interferometry. Georgia Tech’s engineers will build the propulsion systems for a pair of briefcase-sized CubeSats that will fly in orbit a few hundred yards away from one another, bouncing starlight back and forth.

The technology could be used someday to better understand if any known exoplanets are capable of supporting life as we know it.

Interferometry is already used to study stars, gas clouds, and galaxies. Instead of using one large telescope, several smaller telescopes work as a team. The machines swap starlight to create higher resolution images than are possible from a single telescope.

Scientists and engineers have recently proposed using interferometry to locate exoplanets.

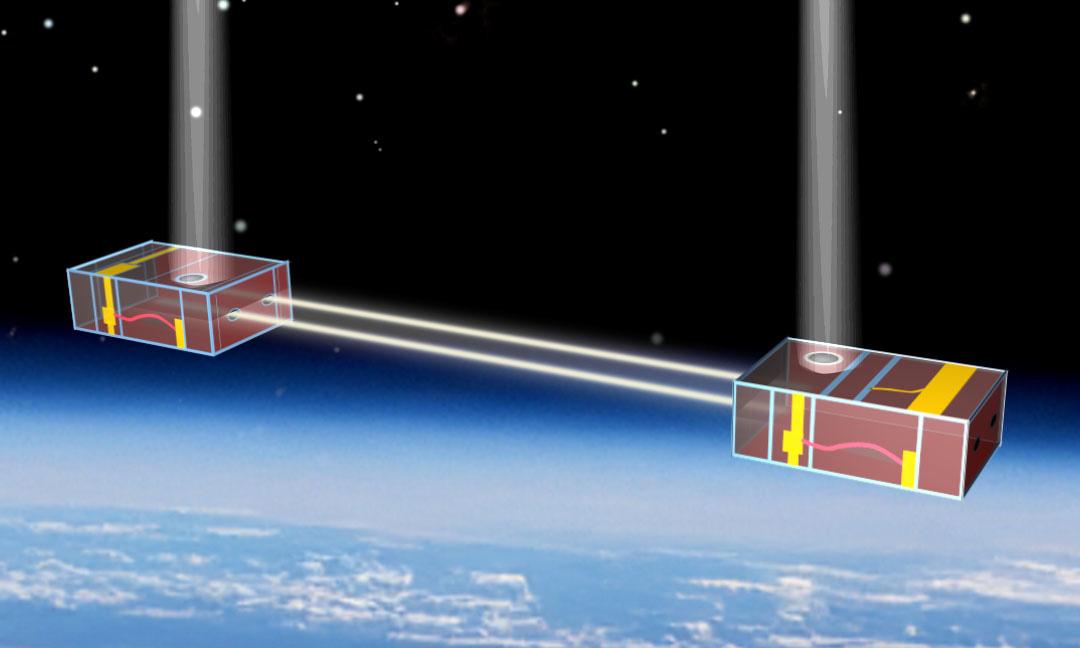

STARI will determine if the same type of coordination and light transmission can be done using less expensive CubeSats. Although STARI won't peer at exoplanets, it will test the ability of small satellites to gather light into a hair-like optical fiber, then beam that light to a partner up to 100 meters away.

The mission's goal is to demonstrate that two CubeSats — STARI-1 and STARI-2 — can send starlight to each other. Credit: Hans Anderson/Michigan News

The satellites will need to maintain their position and orientation relative to each other to within millimeters — roughly the thickness of a dime — while zipping around in a low-Earth orbit.

“STARI is important because of the new technology it will create,” said Glenn Lightsey, the John W. Young Chair Professor in Georgia Tech’s Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering. “We are on the edge of a new era of bringing precision maneuverability to small satellites, and that opens up lots of new mission concepts.”

Lightsey and his students have built and launched several CubeSats and propulsion systems in recent years.

They developed the propulsion for BioSentinel, a small satellite aboard NASA’s Artemis I mission in 2022. The same year, Lightsey’s lab created a propulsion system for Lunar Flashlight, and Georgia Tech led integration of that system with the satellite’s scientific instruments and subsystems. The spacecraft is now orbiting the sun, making Georgia Tech the only higher education institution that owns an interplanetary spacecraft.

STARI will mark the second time Lightsey’s team builds a propulsion system for a Michigan-led mission. The first was for the Sun Radio Interferometer Space Experiment (SunRISE), which launches later this year. Six toaster-size CubeSats will work together to study solar activity.

“Missions like STARI are great for universities like Georgia Tech because they enable more participants in space exploration,” Lightsey said. “The speed of discovery also has increased because missions can now be constructed and launched more quickly."

The STARI team includes researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Stanford University, and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

“We’ve detected thousands of these exoplanets and most by indirect means — in other words, not directly through the light they emit,” said John Monnier, a Michigan professor of astronomy and leader of the project. “It's time to change that.”

The researchers said STARI is part of a larger shift happening in space missions. Rather than packing all the technology a mission needs into a single spacecraft, missions are dividing the load between multiple vessels and even ground-based instruments to accomplish more than previously possible.

“By testing formation flying technologies on a CubeSat platform, STARI paves the way for future missions that could revolutionize our ability to study distant Earth-like planets,” said Gautam Vasisht, a collaborator on the project and a JPL research scientist.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Glenn Lightsey is the John W. Young Chair Professor.

Related Content

CubeSat Propellant Innovation Set to Transform Space Missions

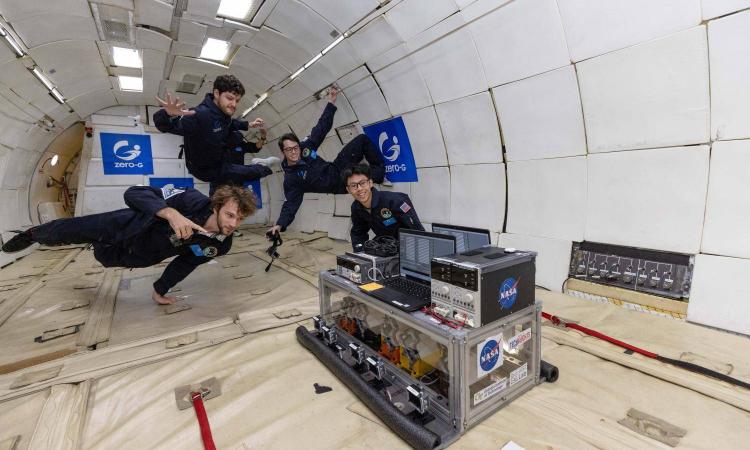

Four aerospace researchers rode aboard a plane in zero-gravity conditions to test payloads and multiphase fluid management technologies.

How Can There be Water on the Moon?

Glenn Lightsey and professors in the College of Sciences explain why frozen water is trapped on the lunar surface ... and why it matters.

(text and background only visible when logged in)