Biomedical engineer Chethan Pandarinath collaborates with neurosurgeons and scientists across the country in a massive project to help patients with ALS or stroke damage reconnect with the world.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

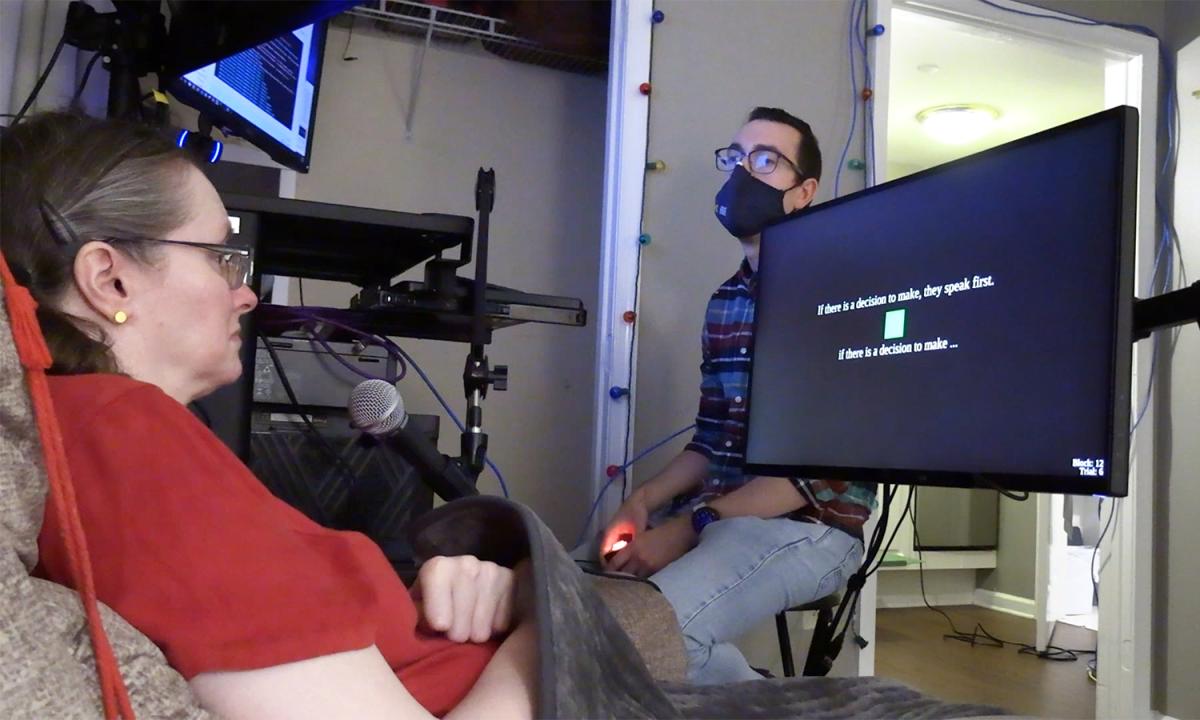

This summer, a team of researchers reported using a brain-computer interface to detect words people with paralysis imagined saying, even without them physically attempting to speak. They also found they could differentiate between the imagined words they wished to express and the person’s private inner thoughts.

It’s a significant step toward helping people with diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, reconnect with language after they’ve lost the ability to talk. And it’s part of a long-running clinical trial on brain-computer interfaces involving biomedical engineers from Georgia Tech and Emory University alongside collaborators at Stanford University, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brown University, and the University of California, Davis.

Together, they’re exploring how implanted devices can read brain signals and help patients use assistive devices to recover some of their lost abilities.

During a research session, a participant imagines saying the text cue on the screen. The bottom text is the brain-computer interface’s prediction of the imagined words. (Photo courtesy: Chethan Pandarinath)

Speech has become one of the hottest areas for these interfaces as scientists leverage the power of artificial intelligence, according to Chethan Pandarinath, associate professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory and one of the researchers involved in the trials.

“We can place electrodes in parts of the brain that are related to speech,” he said, “and even if the person has lost the ability to talk, we can pick up the electrical activity as they try to speak and figure out what they’re trying to say.”

Pandarinath and Emory researcher and neurosurgeon Nicholas Au Yong are now expanding their work to look simultaneously at brain areas involved in speech and hand movements. They’re working with an Atlanta woman who suffered a brain stem stroke, leaving her mostly paralyzed. Sensors implanted in her brain track signals from both areas in an effort to understand — and then recreate — the brain’s natural ability to switch seamlessly between different activities.

“When you move your hand or talk, it just happens. You know what you want to do. You don’t have to press some button to enable speech. Basically, we’re trying to make a brain-computer interface that’s just as easy to use,” Pandarinath said. “People are going to use them for speaking; they’re going to use them for controlling their computer. Can we seamlessly tell when they transition from one to the other?”

Part of doing that is disentangling how brain signals in one area alter other signals. Sometimes the user’s intent is to speak or move their hand. But sometimes, it might be both. Or neither. The challenge — and the hope — is to understand all of that.

Pandarinath said they’re likely the first researchers to look at these two areas of the brain together. The team picked those specific motor functions because their patient has limited hand function and weakened diaphragm control that makes speech difficult.

Meanwhile, they’re also working to simplify how their participant interacts with a computer. Currently, she must think through each step when she wants to move a pointer to click on something on the screen. For example, she would think about moving left until the pointer reaches the destination. Then she might have to think about moving up until she reaches what she wants to click. Only then can she think about clicking it.

Sometimes the user’s intent is to speak or move their hand. But sometimes, it might be both. Or neither. The challenge — and the hope — is to understand all of that.

But what if she could just think about clicking on the object, without all the steps in between?

“You or I might think about reaching out to grab a cup. There’s a higher-level goal, and then we just execute the whole thing — reach out, grab the cup, bring it back,” Pandarinath said. “What we’re trying to do is understand the planning activity so we can offload all the low-level details and just let her be able to think, ‘I want to go click on that thing.’ And then go and do it.”

The researchers can see moment-by-moment activity in the brain. And they can see the split-second planning that precedes it. That might allow them to skip the tedious steps and go right the ultimate goal.

Still, mistakes happen: Their algorithms might misinterpret her intent.

“Let’s say we think she’s trying to move to target A, and instead she actually wants to move to B. What is the process like when she sees what we decided, realizes it’s wrong, and is trying to correct?” Pandarinath said. “We need to understand errors and correction better to make this something that can work really well for her.”

This long-term, multi-site study allows Pandarinath and his colleagues to explore these questions deeply. Each research site works with one patient for a year or more, sharing data and control algorithms. When something works for one patient, they’ll try it with others across the country.

“You get to not only work on developing these devices but also ask a lot of neuroscientific questions. You’re working with somebody a couple times a week for many years, allowing us to study the brain and ask questions that we couldn’t ask in any other way.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

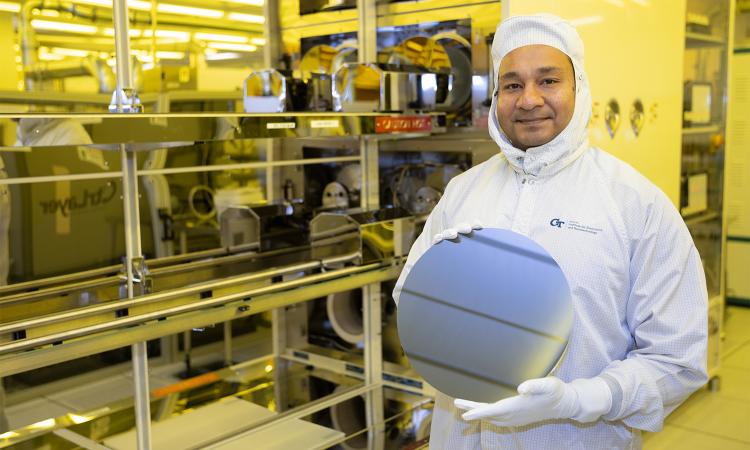

Engineering Next-Gen Computing

At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.

Digital Doppelgängers

Engineers are building computerized replicas of cities, and even Georgia Tech’s campus, to save lives and create a better, more efficient world for all of us.

Wearing the Future

From smart textiles to brain-computer links, Georgia Tech engineers are designing wearables that connect humans and machines more closely than ever to sense, respond, and heal.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Helluva Engineer

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Helluva Engineer magazine.

The future of computing isn’t just about making chips smaller or faster; it’s about making computing better for people and society. And Georgia Tech engineers are shaping that future, designing the processors and memory that will power technologies we can’t yet imagine. They’re using today’s digital power to shape the physical world, helping people live healthier lives, making cities safer, and addressing the digital world’s huge demands on real-world land and resources. Smaller, smarter, faster — the pace of change in computing is accelerating; log into our latest issue to see how Georgia Tech engineers are making it all add up.