Sungmee Park (left) and Sundaresan Jayaraman with the original “Smart Shirt” (right). (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

From smart textiles to brain-computer links, Georgia Tech engineers are designing wearables that connect humans and machines more closely than ever to sense, respond, and heal.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

If you walked through the Smithsonian American History Museum in the mid-2000s, you might have seen the “Smart Shirt,” the very first garment to seamlessly combine textiles and electronics.

Dubbed a “wearable motherboard,” it acted as a hub for sensors that could collect a range of biometric data.

That shirt foretold a future where health and biometric data could be collected unobtrusively through wearable technology. And it was created by engineers at Georgia Tech.

“What we have is all these nice data buses that are the fabric threads. And we can connect any kind of sensors to them,” said Professor Sundaresan Jayaraman, the shirt’s co-creator. “We were able to route information in a fabric for the first time, just like a typical computer motherboard. That’s why we called it the ‘wearable motherboard.’”

Jayaraman and Sungmee Park created the shirt in response to a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) call for ideas to protect soldiers in battle. They envisioned a comfortable, flexible garment infused with fiber optics to detect gunshot wounds and vital signs. The data would help medics rapidly triage battlefield injuries in the critical minutes when emergency care is the difference between life and death.

Creating a shirt made it easy: no bulky electronics to add to the gear soldiers carried. Just a piece of clothing to wear under their fatigues. Park and Jayaraman developed a way to weave the garment on a loom, making mass production and consistency far easier.

The original sleeveless shirt is tucked into the Smithsonian archives now. But it’s possible to follow the thread of that first smart textile to the work happening in the pair’s School of Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) lab today.

What’s More Wearable Than Clothes?

“We looked at textiles as an information processing infrastructure. In other words, our paradigm was, fabric is the computer,” Jayaraman said.

“We are still able to use that fundamental breakthrough,” Jayaraman continued, “looking at fabric as an information infrastructure or a computer, and using it for different applications, whether it is for designing the next generation of respirators, pressure injury prevention, or monitoring hospital patients.”

Park and Jayaraman are creating fabrics and systems these days to detect pressure and moisture experienced by people in wheelchairs or hospital beds. The data can help caregivers move patients to prevent sores on their skin. It could also power automated systems to relieve the pressure at contact points, and they’ve developed a prototype wheelchair that does the same.

They’re also developing small EEG caps for infants, integrating their fabric sensors into a soft, breathable knit cap that would be a safer alternative to traditional setups.

“An EEG cap has a lot of sensors with thick wires. Those wires can cause pressure injuries for a baby,” said Park, principal research scientist in MSE. “There’s also risk of the baby getting tangled in those wires. We are trying to put all those things into a knit cap to collect the EEG data.”

Sundaresan Jayaraman (left) looks at pressure data from fabric sensors he developed with Sungmee Park, who is seated in their prototype wheelchair system. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Park said sensing garments could help older people avoid falls, perhaps with sensors integrated into a headband to identify patterns of movement that make falls more likely. Leggings, shirts, sports bras, and other apparel could monitor muscles, track breathing, and collect other data to help athletes improve workouts or avoid injuries.

“The beauty about clothing is real estate,” Jayaraman said. “You can potentially use the entire body for any kind of sensing you want.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Getting Skin in the Game

While Jayaraman and Park focus on the real estate afforded by clothing, another interface offers potential to sense the world and communicate with the brain. Our skin also has plenty of real estate — and an incredible range of abilities that Assistant Professor Matthew Flavin in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) wants to capitalize on.

Flavin uses haptic devices to deliver vibration, indentation, and twisting sensations to help people with vision loss navigate their environment. He’s also working to improve balance for people who’ve lost feeling from a stroke or spinal cord injury.

Flavin calls his team’s work “epidermal virtual reality” — using custom-designed devices to provide users with information. He describes it as creating a realistic sense of physical touch akin to the way virtual-reality headsets create realistic visual information.

Haptics might be familiar as the feedback a smartphone provides while typing or tapping or from playing video games, where a controller vibrates in response to actions on screen. Flavin is taking that concept further with arrays of small, wearable actuators that poke, vibrate, or twist.

“Just like our eyes have multiple different receptors, which can sense red, green, and blue, our skin has these different receptors that can sense indentation, vibration, twisting,” Flavin said. “These are all things that we want to deliver with really small-scale devices we’re developing.”

One area of work pairs a hexagon-shaped patch of haptic actuators on the back of the neck with a smartphone’s camera and LiDAR sensor. People with vision impairment scan the area around them with the phone and receive a small vibration to alert them when an object is detected. For example, a chair sitting low to their right would activate haptics in the lower right area of the patch.

It offers richer information than conventional aids like canes. In trials, a blindfolded subject navigated an obstacle course using only the device without bumping into anything.

Flavin and his team have modified the same structures to provide a twisting sensation, as well as pokes or vibration. They can do it without a huge battery or being plugged in — an improvement over other devices. He said adding the additional twisting “channel” of information can make using the device much more intuitive.

“We use torsion as a navigational signal, telling people how to navigate towards a particular object, and then indentation as a corrective signal, telling people that they want to avoid a particular object,” Flavin said. “Having both of those can give you navigation information in a very efficient way.”

Another study uses forearm haptics connected to shoe insoles to help stroke or spinal cord injury patients who’ve lost some sensation in their feet.

“Those haptic devices deliver a pattern of vibration that matches the pattern of pressure they’re putting on their foot in real time. That should help them with some of those motor and sensory symptoms: We’re substituting that plantar pressure information to help those patients balance and walk with a healthier gait,” Flavin said.

Worn on the neck, and paired with a smartphone, the actuators can help people with vision loss navigate their environment. (Photo: Chris McKenney)

Beyond haptics, Flavin’s team has created a small wearable sensor that detects gas exchange across the skin. It can reveal a lot about skin’s health, including whether it’s properly working as a barrier and how well it’s repairing itself. For people with diabetes, the sensor could offer early warning that wounds aren’t healing, a common problem that can lead to serious consequences — even amputations — if not dealt with quickly.

“Our skin is our largest organ, and we have sensory receptors across the entire surface. It’s really underutilized as a human-machine interface,” Flavin said. “We can use haptics to deliver information to our body. We can also get a lot of information from our skin.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Expanding from Sensing to Intervention

Millions of people already get daily haptic feedback from a smartwatch or fitness device.

Omer Inan says the ability of these popular wearables and their sensors to impact health is just beginning. Inan is the Linda J. and Mark C. Smith Chair and professor and a Regents’ Entrepreneur in ECE. And he says the game is changing, pointing to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of the Apple Watch’s ability to detect signs of atrial fibrillation or the Samsung Galaxy Watch’s detection of sleep apnea.

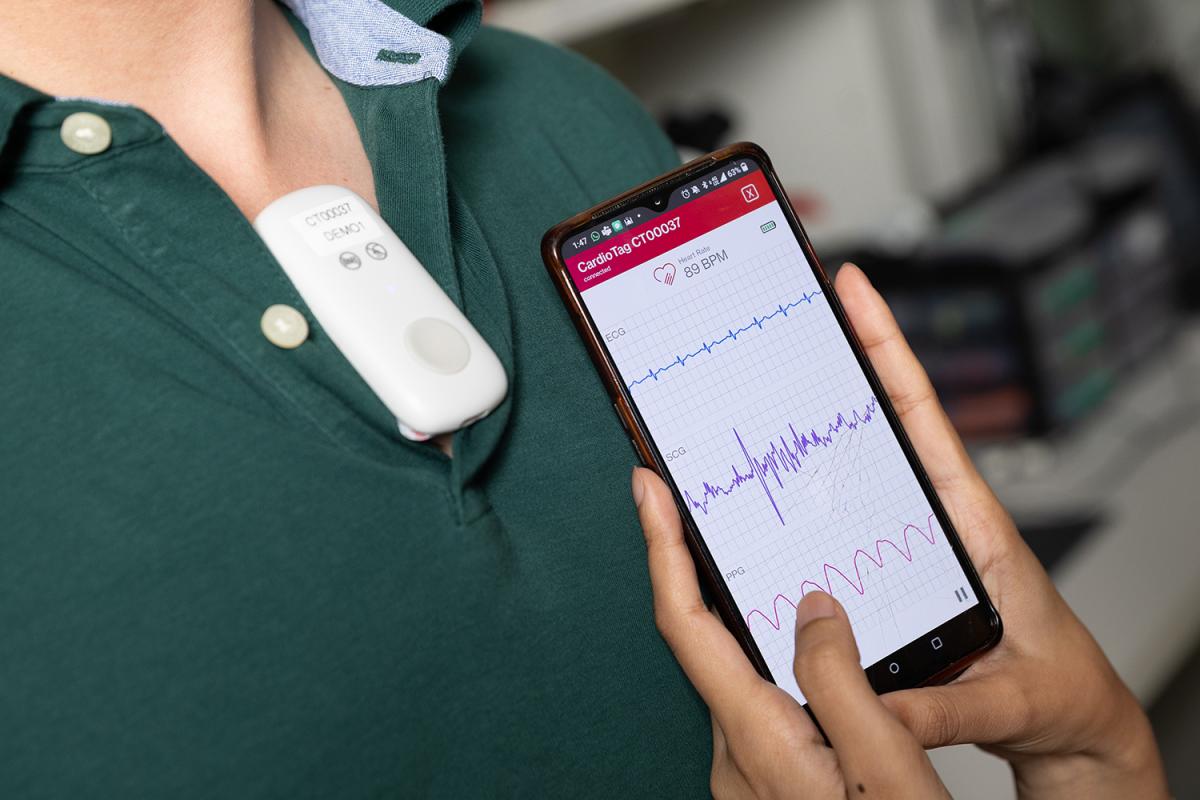

The CardioTag device relays three different heart readings (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Those clearances aren’t for the devices but for underlying software that uncovers issues in data collected by the devices. It’s an area his lab is deeply involved in: He’s spun out a number of startup companies developing both clinically relevant devices and software to use their data.

One of those devices is the CardioTag, a sensor that captures three heart signals and received FDA clearance this summer. The company Inan co-founded to commercialize the sensor is using it in a study to validate software that assesses pulmonary capillary wedge pressure — a measure of how well the heart fills with blood. It’s one way CardioTag’s data can deliver useful data to physicians. But Inan said that’s just the beginning.

“For us, what’s more important is that the same hardware can be used with multiple different software clearances,” he said. “Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is a really important parameter for heart failure that affects about 6.5 million Americans. But we could look at software to measure cardiac output or arterial blood pressure. There are many different software clearances from the FDA that could work with the same hardware, which makes it completely modular.”

Another device Inan is working on would help calm the stress reaction for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It’s a wristband that senses physiological changes and delivers electrical stimulation to specific nerves to counteract it.

He said targeting the median nerve in the wrist can begin to blunt the body’s overreaction within 10-15 seconds in their lab tests.

“We found if you electrically stimulate at the wrist, you do actually reduce the body’s peripheral response to stress. The mechanisms are not well understood, but we see it in the data,” Inan said. “It’s why we developed a wearable that both senses from the wrist and stimulates.”

Helping PTSD patients is one significant area, with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimating about 6% of Americans will have PTSD at some point in their lives. But modulating overwhelming stress could have much wider uses, Inan said.

“There are stress-related anxiety disorders, which affect even more people. And too much chronic stress is a problem even for healthy people. So this may even be beneficial for those who don’t have any of those stress disorders,” he said. “That’s speculative still, but there are millions of people who could benefit from such a device.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Omer Inan (left) and Ph.D. student Farhan Rahman make adjustments to a prototype wristband that would sense a rising stress response and deliver electrical stimulation to counteract it. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Networking In and On Our Bodies

Inan’s stress wristband illustrates how wearables can sense and respond. Imagine if external smart devices and sensors could also communicate with implants or ingestible devices to deliver treatment inside the body too. That’s the vision driving Assistant Professor Alex Abramson’s research in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

What might that look like?

In a serious allergic reaction — the kind that requires immediate medical treatment or administration of epinephrine via an EpiPen — sensors would detect the allergic response and trigger a small device in the body to administer the epinephrine in the right dose and at the right place.

For people with chronic diseases or cancer, the devices would monitor specific health indicators and apply therapies as needed. Creating interactions between wearables and implants could detect nerves firing and then move a prosthetic limb.

Alex Abramson (right) works with grad students Ramy Ghanim (left) and Joy Jackson to test an implantable device. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

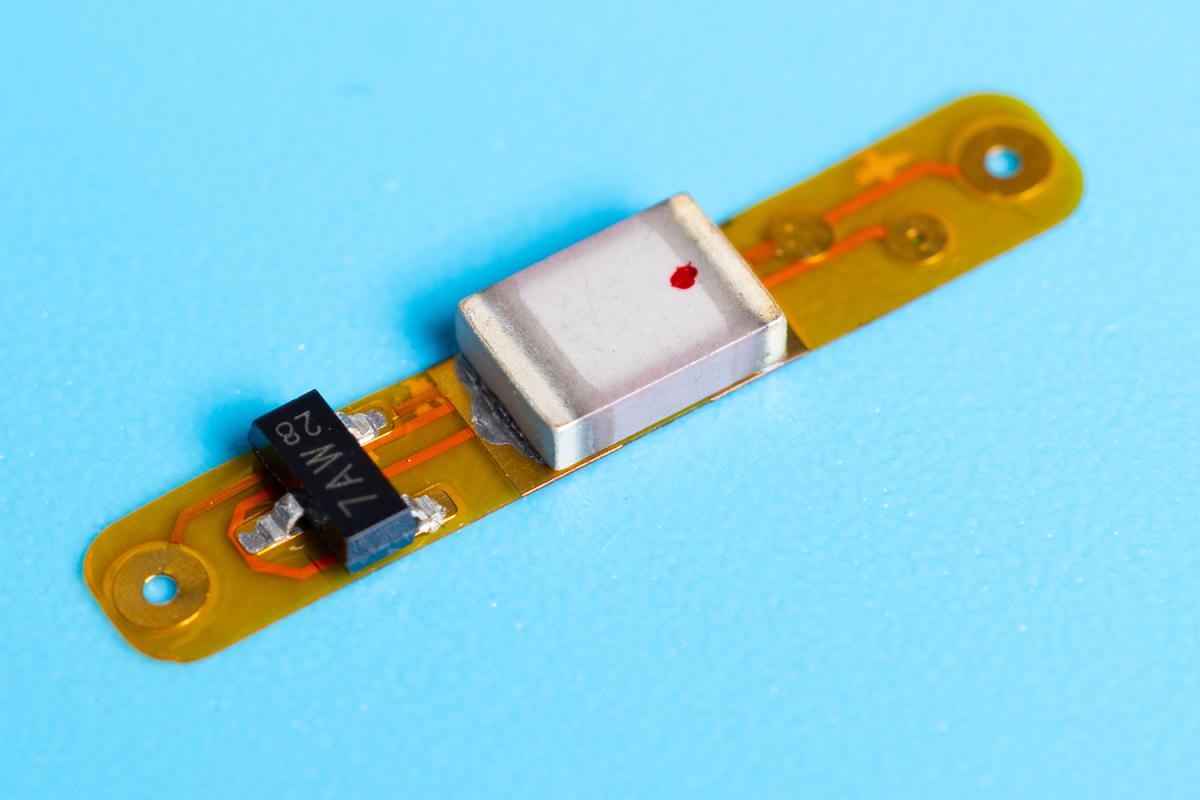

The implantable device can communicate with external smart devices and sensors. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

“What’s really difficult is taking that wearable information and allowing it to actuate a therapeutic device inside your body,” Abramson said. “We work on creating devices able to deliver drugs or a therapeutic interaction at the exact location and time you want, without causing any off-target side effects. We also create the network that allows for those devices to interact with wearable sensors others are creating.”

Abramson’s team capitalizes on all the fluid and salts we’re made of to build a communications infrastructure. They make it easy to pass a small electrical signal through body tissues that can be detected by an implant and trigger it to act. Abramson said the method is 30 times more energy efficient than Bluetooth. That means implants can be smaller and last longer.

“We’re able to trigger devices anywhere throughout the body instead of needing direct interaction between the wireless antenna on the outside and the implantable on the inside,” he said. “It also allows us to create a full network of these therapeutics: Because we’re able to trigger anything, anywhere inside of the body, all from a central hub, we can have these devices work in tandem as well.”

The size advantages of Abramson’s in-body communications system mean they can scale implants down to about 3 millimeters in diameter — small enough to be implanted using a syringe instead of surgery.

Meanwhile, the ingestible devices his team is developing are designed to target specific locations in the gastrointestinal tract. They linger in the stomach and can orient themselves so they’re right next to the tissue where they need to deliver medicine or even a small electrical stimulus.

Abramson said emerging data suggests such stimulation directly in the gut can improve mood and reduce stress levels. Stimulation also can prompt the stomach to empty properly, which sometimes doesn’t happen for people with diabetes.

The inspiration for Abramson’s vision of networked devices all working together to diagnose and treat acute or chronic conditions is the insulin pump. It’s a “closed loop” system where a sensor continuously monitors blood glucose and triggers a dose of insulin when needed. The problem is other commercial sensors aren’t as good as the glucose sensor. And the pump requires lots of energy and computation power.

“That’s really the gold standard of what we’re trying to emulate for all of our other different types of diseases,” he said. “Imagine something like an insulin pump but implanted inside of your body and able to treat neurodegenerative diseases, heart disease, cancers, or any other types of chronic illnesses.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Sleep Sentinel

Many of those chronic illnesses show up as disturbances in our sleep. Detecting them, however, is onerous. And that’s putting it mildly, according to W. Hong Yeo. Despite the “sleep score” you might get from a smartwatch or fitness tracker, the only way to get reliable data to diagnose sleep problems is an expensive night in a sleep lab.

It’s cozy: Patients are connected to dozens of sensors and observed all night. If the sensors disconnect as they move — and they often do — a technician has to reconnect them. Plus, it’s only one night.

“From the beginning, it doesn’t make sense,” said Yeo, Harris Saunders Jr. Professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “It’s not capturing your natural sleep. Nobody can sleep well in a sleep lab. But that’s the only way, because of limitations of technologies and available devices.”

Yeo has been working for years to change that, and he’s closer than ever to bringing the gold-standard lab techniques home with a trio of wireless devices that can capture the same data over multiple nights to get a better picture of natural sleep behavior. He created a startup company to pursue FDA clearance for the technology and get it in doctors’ hands.

Instead of wires and sensors from head to toe, Yeo’s Technology Enhanced Dreaming (Tedream) system uses three soft, flexible sensors attached to the forehead, chest, and forearm. They collect data on brain activity, heart rate, posture, respiration, sound, blood oxygen, and movement, feeding it wirelessly to a nearby tablet.

Hong Yeo’s Tedream system includes three soft, flexible sensors that can collect sleep data comfortably and at home — rather than in a sleep lab. (Photo courtesy: Wismedical)

“This is the complete package of sleep. Our system will give you everything that you need in terms of diagnostics. Then the doctor can make decisions about how severe symptoms are and therapeutic options,” said Yeo, who also is the G.P. “Bud” Peterson and Valerie H. Peterson Endowed Professor.

“It will change the paradigm of measuring sleep quality and sleep disorders once it’s available.”

It’s a problem that hits close to home for Yeo, whose father had a heart attack and died in his sleep two decades ago. He had no history of heart issues, but Yeo realized better data about sleep could’ve alerted his dad’s doctors to an issue.

“That’s why I’m doing my best,” he said. “I strongly believe that this type of device will save a lot of lives.”

Hong Yeo’s brain-computer interface fits between hair follicles on the scalp. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Yeo’s work has resulted in a variety of flexible electronics and sensors, including a smart stent for monitoring blood pressure and blood vessels and a smart pacifier to measure babies’ electrolyte levels from saliva instead of repeated painful blood draws.

He’s also working on a new kind of brain-computer interface that’s so tiny it fits between hair follicles on the scalp. In a recent study, it captured high-fidelity signals that allowed subjects to control an augmented reality video call. He sees potential for the interface to allow users to manipulate robotic devices or prosthetic limbs — without having to implant sensors in the brain.

Like many of the Georgia Tech engineers working to imagine new wearable devices that will address difficult health challenges, Yeo collaborates across campus and with researchers and doctors at Emory, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and elsewhere. That, he said, is the secret to having real impact.

“Without them, I couldn’t make any of this happen. Collaboration is really important when it comes to making a new innovation, because existing problems are so complicated that they cannot be solved by one person.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

Engineering Next-Gen Computing

At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.

Digital Doppelgängers

Engineers are building computerized replicas of cities, and even Georgia Tech’s campus, to save lives and create a better, more efficient world for all of us.

Allowing the Paralyzed to Communicate Again

Biomedical engineers, neurosurgeons, and scientists are collaborating on better brain-machine interfaces to help patients with ALS or stroke damage reconnect with the world.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Helluva Engineer

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Helluva Engineer magazine.

The future of computing isn’t just about making chips smaller or faster; it’s about making computing better for people and society. And Georgia Tech engineers are shaping that future, designing the processors and memory that will power technologies we can’t yet imagine. They’re using today’s digital power to shape the physical world, helping people live healthier lives, making cities safer, and addressing the digital world’s huge demands on real-world land and resources. Smaller, smarter, faster — the pace of change in computing is accelerating; log into our latest issue to see how Georgia Tech engineers are making it all add up.