(text and background only visible when logged in)

Engineers are building computerized replicas of cities, and even Georgia Tech’s campus, to save lives and create a better, more efficient world for all of us.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Extreme weather, congested streets, aging infrastructure — just some of the challenges that communities and their residents face every day. Solving them requires more than traditional planning; it demands tools that can anticipate problems before they happen.

One of the tools our researchers are turning to is called a digital twin. These virtual models mirror real-world systems in real time to make communities safer, transportation smarter, and campus operations more efficient.

Unlike static simulations, digital twins evolve with live data. They allow decision-makers to respond to changing conditions with speed and precision. Whether it’s predicting how floodwaters will move through a city or minimizing traffic delays for emergency vehicles, digital twins offer a new way to manage complexity. By blending artificial intelligence, sensor networks, and advanced analytics, Georgia Tech engineers are creating solutions that don’t just react — they prepare, adapt, and improve the systems we rely on every day.

Technology Amid a Triple Threat of Flooding

From their office high above Tech Square, John Taylor and Neda Mohammadi can see more than a hundred miles on a clear day. Their focus this fall, however, expanded well beyond the horizon.

The School of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) researchers have been watching the tropics and their impact on Charleston, South Carolina. This hurricane season was the first for a series of sensors in the city that track flood water levels and their impact on the city’s historic streets.

The duo’s research team built a digital twin of downtown Charleston that shows every road and block of the low-lying peninsula. It uses artificial intelligence and geographical information system analytics to predict flood impacts on roads. The flood risk visualization, which also incorporates road closures due to high waters, allows city officials to reposition emergency vehicles during flooding, a common occurrence.

The idea to approach Charleston County leaders was born after Taylor and Mohammadi successfully deployed a digital twin of the Chattahoochee River for Columbus, Georgia, that helps search and rescue workers save lives when the water rises quickly.

“Columbus gave us experience with rising water levels and made us think about places where a similar concept could be applied more broadly,” said Taylor, Frederick Law Olmsted Professor in CEE. “It led us to Charleston, which has a triple threat of flooding.”

Charleston is framed by the Atlantic Ocean and two rivers: the Cooper and the Ashley. Tidal creeks from those rivers flowed into the peninsula hundreds of years ago. But as the city became more populous in the 18th and 19th centuries, the creeks were filled with trash, materials from old ships, and other debris to create more areas to live and work.

Those filled-in creeks are now the lowest points in the city and include some of the peninsula’s major roads. That’s a problem when heavy rains and high tide pound the city. The water flows directly to those low areas and floods. Even worse: one of Charleston’s main hospitals is surrounded by those low-lying roads.

John Taylor and Neda Mohammadi (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

Georgia Tech worked with researchers from Clemson University and the University of Hawaii to place several traditional flood sensors in the city to measure how much water is present, including on the roads near the hospital.

Meanwhile, another set of sensors measuring the flood levels are much different. With a unique vision-based sensing approach, the CEE team uses video livestreaming data from cameras coupled with an AI visual language model they developed to detect how deep the water is.

This hurricane season is their first with everything in place. They’re not hoping for bad storms — but every rainy day helps.

“Every time it rains, our ability to predict road closure risk improves. It also improves our models and makes them more applicable to other places. And it helps us see if the sensors are working as planned,” Taylor said.

... digital twins can give you different results every hour because they’re based on real-time numbers. This allows city officials and communities to make decisions based on evidence instead of past events.

NEDA MOHAMMADI

The digital twin also allows the team to play “what if,” and feed that information to Charleston officials. For example, they can simulate 6 inches of rain or 24 inches or anything in between and see how it impacts roads and typical ambulance routes.

By using real-time data, they can see results shift as conditions change.

“Simulations don’t change if you run them week after week, but digital twins can give you different results every hour because they’re based on real-time numbers,” said Mohammadi, a senior research engineer who wrote her first paper about cities and digital twins in 2017. “This allows city officials and communities to make decisions based on evidence instead of past events. We bring them real data that produces informed, hyper-local decisions.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

In the Shadows of Campus

While Taylor and Mohammadi are using a digital twin to explore the macro level of a city’s road network, their CEE colleague Angshuman Guin is zoomed in on the micro level. He and his students are looking at each car that rolls along Atlanta’s North Avenue adjacent to campus.

They’re using recorded drone footage and live cameras to track how each vehicle interacts with the hundreds around it as they pass by campus or exit the Downtown Connector.

Like the Charleston project, Guin’s digital twin is designed to save lives. By understanding how long it takes motorists to move through North Avenue’s series of traffic lights, Guin and his team hope to lessen delays for ambulances headed to nearby Emory University Hospital Midtown.

His technology helps clear intersections before ambulances and fire trucks arrive. It was first developed in collaboration with the fire department and the transportation department in Gwinnett County, Georgia. It also inspired a $5 million statewide initiative funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

“If we can predict when and where an emergency vehicle will need to pass — and clear the path in advance — we’re saving minutes that can mean saved lives,” said Guin, a CEE principal research engineer who received his master’s degree and Ph.D. from Georgia Tech.

The team has a variety of ways to use their data for predictive modeling. First, they use the drone footage to observe the second-by-second movement of vehicles. They can see the interactions between emergency and regular vehicles and build driver-behavior models that inform large traffic simulations. Those models allow Guin’s team to study alternative scenarios and traffic operation strategies.

The second tactic is a pseudo digital twin. Guin has been collecting data from North Avenue for several years and can feed any day’s worth of data into a simulation, then play it back second by second. Data is driving the simulation, but it’s not live synched with what’s happening on North Avenue.

Angshuman Guin studies data from his digital twin of North Avenue. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

The third is a true hardware-in-the-loop digital twin, which allows for near-real-time data simulation. Whenever a vehicle drives along North Avenue, a streetside detector feeds that signal to Guin’s team. By working with live data, the digital twin goes beyond a typical simulation and allows for testing of new strategies on real field equipment, but in a virtual environment. For example, the AI model can try different signal lengths at its virtual intersections to see how drivers respond. Once the team runs enough simulations to be confident with the results, they can try them on the real North Avenue.

“Prioritizing an emergency vehicle can be done fairly simply by giving a green signal to all the intersections on its path, then holding the signal until the vehicle passes,” Guin said. “But that causes driver angst and potential safety issues when vehicles start violating red signals after long wait times at a signal with no apparent crossroad traffic. Our digital twin is really about development and testing of algorithms that will serve both objectives of concurrently minimizing emergency vehicle delays and reducing general traffic delays.”

Guin said he’s lucky his real-world laboratory is so close to his lab in the center of campus. North Avenue has it all: it’s a southbound exit portal for one of the busiest interstates in the southeast; it has two eastbound turn lanes that lead to the Connector, and it’s a main thoroughfare for the hospital.

“It truly has everything a traffic engineer could want,” Guin said. “It’s a big puzzle, and we hope to solve some of its pieces and make things a little better for everyone.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Tech Twinning

Two more digital twins live within the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering, although neither has anything to do with space exploration or the future of flight.

Research engineers in the Aerospace Systems Design Lab (ASDL) have supported the development of a digital twin of Georgia Tech’s AI Makerspace, the nation’s most powerful supercomputing hub used exclusively to teach students. The Makerspace’s 304 NVIDIA H100 and H200 GPUs are being incorporated into several undergraduate AI courses, including the Fundamentals of Machine Learning and AI Foundations.

ASDL’s Olivia Fischer and Scott Duncan, along with Aaron Jezghani from Georgia Tech’s Partnership for an Advanced Computing Environment (PACE), have used the digital twin to visualize and communicate about computational resource use and impact. They’re also working with a team of Georgia Tech students and thinking about how they can use the twin to improve the Makerspace’s operational efficiency and manage its infrastructure.

“As the use of AI continues to grow in both academic and research settings, such capabilities could offer Georgia Tech’s leadership a comprehensive and detailed picture of asset utilization and support data-driven investment decisions that anticipate the growing needs of researchers, both inside and beyond the classroom,” said Fischer, a principal research engineer.

Olivia Fischer

Dimitri Mavris

The AI Makerspace is only the first step. After using the current digital twin as a proof-of-concept, the research group plans to produce a twin of the entire Coda data center, which houses 2,200 servers in a 2 megawatt footprint. The building serves as Georgia Tech’s headquarters for data analytics research — the processing, handling, manipulation, and understanding of very large data sets across a wide variety of industries and academic disciplines.

For over a decade, ASDL Director Dimitri Mavris has spearheaded the development of digital twins across a range of applications. One of his first emerged from a collaboration with the Office of Naval Research. Mavris and his team developed an integrated electrical-thermal model that digitally represented the power architecture of a naval destroyer. They coupled this model with an interactive dashboard displaying real-time performance data from various ship zones.

The thinking was, if the Navy could collect sensor data from smart valves and other onboard technologies, digital twins could enhance predictive maintenance by allowing for earlier fault detection and better informing maintenance decisions. This predictive capability would, in turn, help reduce maintenance loads, improve operational efficiency, and lower mission failure risks, eventually enabling the Navy to achieve its objectives more effectively and affordably.

The Navy project reminded Mavris of Georgia Tech’s buildings.

“Before the 1996 Olympics, campus began to modernize its energy systems, including installing meters measuring electricity, chilled water usage, and steam usage,” said Mavris, Distinguished Regents’ Professor and Boeing Professor of Advanced Aerospace Systems Analysis. “New buildings that came online later were further outfitted to collect data on their utility performance. The problem was, however, that the use of this data was very siloed. Planning and strategic-level decisions were not accounting for campus-wide energy interactions across all buildings.”

That prompted ASDL to create a digital twin of the entire campus. It compared buildings and, over time, showed when they would start to overconsume energy or use chilled water inefficiently. A related dashboard revealed which buildings weren’t adjusting energy use at night, when students, staff, and faculty had gone home.

“Campus managers got a better sense of when our utility bills were too high or low,” Mavris said. “Our digital twin has helped campus lower costs, improve reliability, and make more strategic decisions.”

During the 2020 pandemic, digital twinning played an important role in the Living Building certification process for The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, one of the world’s greenest buildings. The Kendeda Fund offered Tech a bonus if it could achieve certification within the first 12 months of operation. But in the fourth month, campus shut down, drastically changing the building’s occupancy.

Nevertheless, a digital twin of the building was able to confirm that the building would easily have been net-positive for energy and water, key requirements for certification.

Building on its initial focus on campus energy systems, the campus digital twin expanded to include campus mobility and safety planning. Mavris said the Georgia Tech Police Department has leveraged that information to anticipate areas with a higher likelihood of crime and to manage traffic flow around campus, particularly before and after football games and Commencement ceremonies.

The predictive capabilities of the digital twin also allow campus leaders to project expansion phases and it provides insights into road safety improvements and campus transportation planning. Applying the same digital twin technologies developed for Georgia Tech, Mavris and his team are now assisting the Georgia World Congress Center and Mercedes-Benz Stadium with traffic and safety planning efforts in preparation for the 2026 FIFA World Cup.

“Digital twins represent the bridge between the physical and digital worlds, where data, modeling, and human insight converge to drive decisions that realize value,” Mavris said. “As systems grow more complex, their value will only increase, helping us to predict outcomes, optimize performance, and design solutions that are both sustainable and resilient for the future.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

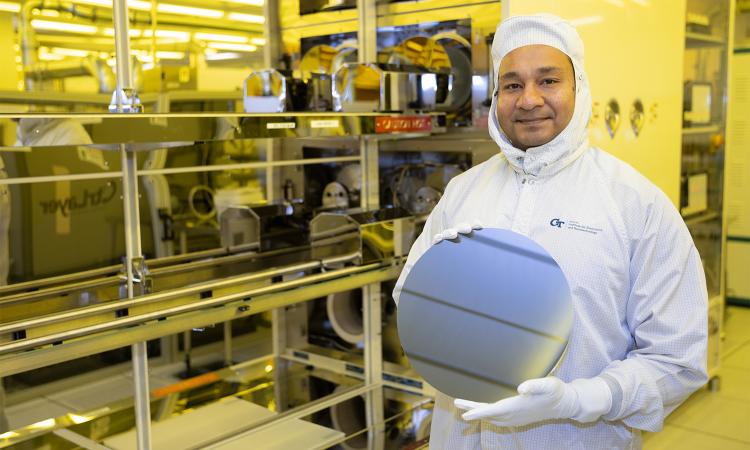

Engineering Next-Gen Computing

At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.

Wearing the Future

From smart textiles to brain-computer links, Georgia Tech engineers are designing wearables that connect humans and machines more closely than ever to sense, respond, and heal.

Moving Toward a Connected, Autonomous Future

How we get around is changing as new options like autonomous vehicles arrive in earnest. Srinivas Peeta works to unravel what that means for our communities and how we plan for a more connected future.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Helluva Engineer

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Helluva Engineer magazine.

The future of computing isn’t just about making chips smaller or faster; it’s about making computing better for people and society. And Georgia Tech engineers are shaping that future, designing the processors and memory that will power technologies we can’t yet imagine. They’re using today’s digital power to shape the physical world, helping people live healthier lives, making cities safer, and addressing the digital world’s huge demands on real-world land and resources. Smaller, smarter, faster — the pace of change in computing is accelerating; log into our latest issue to see how Georgia Tech engineers are making it all add up.