(text and background only visible when logged in)

The massive computing facilities popping up across the country have become notorious for requiring huge resources. These engineers are thinking about how data centers can be more efficient and how they influence our future power needs.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Not too many years ago, most of us didn’t think much about the computing resources required to make a Zoom call, stream the latest hit show, or scroll our social media feeds.

The growing power of artificial intelligence systems — which are exploding in capability and use — has changed that. New data centers are sprouting all the time to power AI models, with especially high concentrations in the Atlanta area and northern Virginia. Powering those centers is straining the grid: the largest and most complex could require the same amount of electricity used by entire cities.

That’s why several of the biggest AI developers, including Meta, Google, and Microsoft, have announced plans to build their own power plants or restart shuttered nuclear facilities solely to power their AI data centers.

The AI models themselves also keep getting more complicated, which means they require more power and cooling, even as computer chips get more efficient.

Georgia Tech engineers are thinking about data centers from a variety of angles, including how to use resources more efficiently and developing ways to provide more power to the grid to meet the surging demand.

Scaling Intelligently

Data centers can occupy hundreds of acres, with unending racks of high-powered computers processing AI models with billions or trillions of parameters. But the truth is, every graphics processing unit (GPU) chip isn’t hard at work every second. Chips also vary in their speed and how much heat they can tolerate, even when they’re the same type.

Divya Mahajan in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering sees huge potential to capitalize on those variations. She’s working to optimize the models themselves and improve how data is accessed and executed to achieve significant efficiency in the resources data centers need in the first place.

Significant, as in five to 10 times more efficient than today.

“It is a hard thing to do though. Because you need to know information from across the computing stack, and you need to work collectively and, sometimes, in lockstep,” said Mahajan, the Sutterfield Family Assistant Professor. “A lot more people need to interact with each other to make data centers more efficient than we’ve had.”

This kind of “cross-layer” optimization allows her to think about ways to make the AI software itself more streamlined, how to improve its execution, the hardware architecture it works on, and even how data is stored and retrieved within data center systems.

Because all of those layers can talk to each other, Mahajan said they should. But that means the engineers who design AI models have to understand how they run on the hardware systems. The engineers building chips have to think about the software that will run on them. And engineers designing data centers need to consider the hardware and software interactions too, not just building facilities with more and more computing power.

Traditionally, each of those players would make their “layer” as good as possible in isolation. Collaborating would mean continuing to grow computational power while reducing energy and infrastructure demands, Mahajan said.

Divya Mahajan (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

“The future of AI depends not only on better models, but also on better infrastructure,” she said. “To keep AI growing in a way that benefits society, it’s important to shift from scaling that infrastructure by brute force to scaling it with intelligence.”

Mahajan offered a simple example of the kinds of efficiencies that can be exploited: Millions of subscribers bingeing the latest hit series on Netflix, while older movies see a fraction of the demand.

“There are all of these nuanced patterns that we can exploit to use the infrastructure — the hierarchy, the memory, the data exchange between devices — a lot more efficiently. And we can exploit those patterns at the model level, the data level, the execution level, and the hardware level,” Mahajan said. “If you look at more nuanced properties that are rooted in even human behavior, you can do things more efficiently instead of just assuming that every data point, every one and zero in the hardware, is the same. It’s not the same. Some ones and zeros you will access frequently; others you will never care about.”

... if you have visibility of the full pipeline comprising different pieces, you can optimize better rather than just having one piece and optimizing that.

DIVYA MAHAJAN

Mahajan creates dynamic runtime systems to use those patterns in the background to boost efficiency. For instance, frequently accessed data can be stored closer to the GPUs that process it so it’s easier to get to and compute. This level of control can help reduce heat generation and energy demand. It can also capitalize on uneven usage, shifting processes from busy computing resources to idle chips.

The next step in her work, which is funded by both software and hardware makers, is to shift from controlling just the software side of things to the physical data center systems. Eventually, Mahajan wants to be able to do things like leverage sensing information around chips and data centers to identify hotspots and adjust cooling systems to target them.

This kind of full-picture approach to operating data centers is why companies such as Google, OpenAI, and others are starting to invest in power infrastructure, she said.

“They understand that if you have visibility of the full pipeline comprising different pieces, you can optimize better rather than just having one piece and optimizing that.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Baratunde Cola (Photo courtesy: Carbice)

Tackling Heat

A big driver of the energy needs for data centers comes from managing all the heat that racks of high-powered chips generate. Cooling systems use air or water to pull that heat away, but in either case, electricity drives those systems.

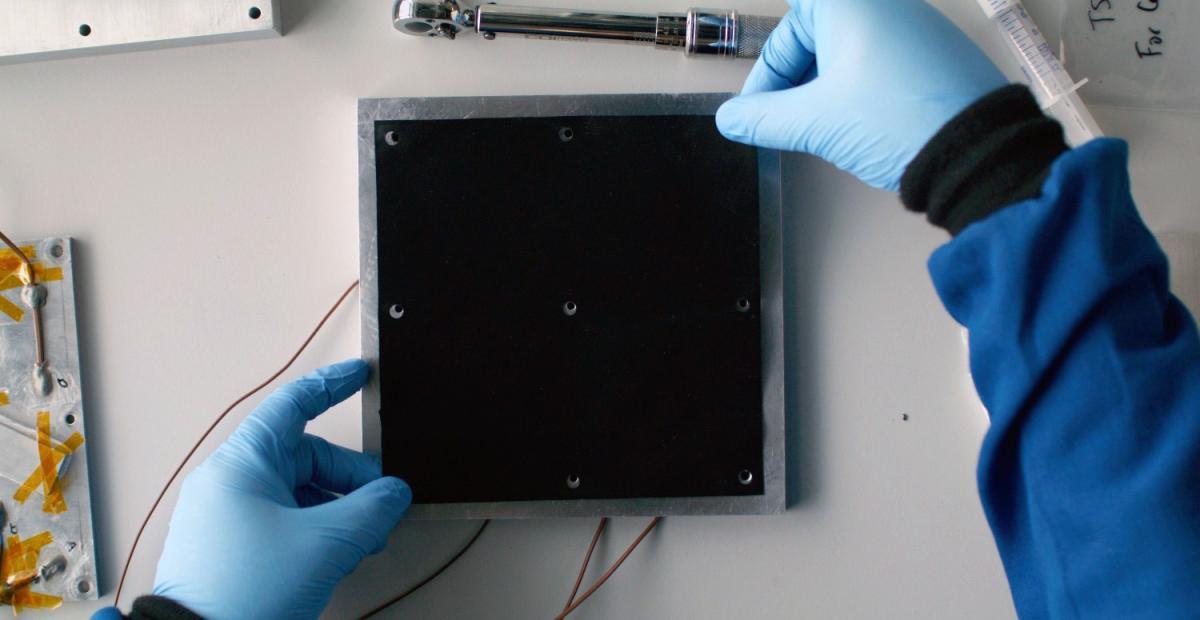

Baratunde Cola has been thinking about how to move heat away from semiconductor chips for a long time — long before data centers became a hot topic. His team has spent years developing a material made for this moment: arrays of carbon nanotubes lined up vertically on an aluminum backbone that are super-efficient at channeling heat.

Cola, an entrepreneur and professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, originally had smartphones and laptops in mind — as well as military applications, thanks to early funding from the Defense Department. But he also knew the time was coming when processors would be so power-hungry that dealing with the resulting heat would be a challenge.

“I wasn’t thinking data-center scale; I was just thinking about wherever power density was high. Performance is proportional to power density, so if you ever want more performance, power density only goes up,” Cola said. “I knew we needed to develop advanced solutions.”

Cola has turned his carbon nanotube arrays into a startup spun out of Georgia Tech called Carbice where he is founder and CEO. The company is manufacturing and selling the material as a thermal-interface solution for data center hardware, spacecraft, and even gamers who can incorporate the cooling technology into their custom-built computers.

Carbice’s carbon nanotubes are arranged into thin sheets that can be cut to size and applied as a simple peel-and-stick pad. They sit right behind a heat source, such as a GPU chip, connecting it to a cooling system or heat sink and channeling heat away. For data centers, designing with Carbice’s technology from the get-go can offer 40% better performance, Cola said. It also might allow for centers to be smaller in the first place — and therefore require fewer resources.

“The industry is ripe with redundancy,” he said. “When someone builds out a data center, they have to plan for 30% to 40% more hardware. That’s the way they deal with failures. When people talk about a data center’s ‘uptime,’ they don’t mean that the actual equipment stays up. They mean they have redundancy. But you lose something in that, because every time you switch and swap, you interrupt operations.”

Carbice’s carbon nanotubes are arranged into thin sheets that can be cut to size and applied as a simple peel-and-stick pad. (Photo courtesy: Carbice)

For data centers, designing with Carbice’s technology from the get-go can offer 40% better performance. It also might allow for centers to be smaller in the first place — and therefore require fewer resources.

Cola said many of those equipment issues result from the failure of the joint between the semiconductor chip and the cooling system behind it. Manufacturers often use special heat-conducting greases or epoxies in that joint that degrade, dry out, or crack over time. Replacing them pulls part of the data center out of service and requires a technician to disassemble the system, reapply the grease, then put it all back together.

Carbice’s carbon nanotube pads don’t degrade, so downtime for those joint issues is significantly reduced and computing power stays online, Cola said. It also means saving on another limited resource: human time.

Cola said that kind of servicing will only grow as power and heat loads in data centers spike as a result of processors running resource-hogging AI.

“That’s where mechanics and what we focus on comes into play: It’s really use conditions that cause joints to fail — like your shoe sole or paint on your wall. Paint can last 50 years in one house but five years in another. Michael Jordan’s basketball shoes probably needed to be changed every few weeks,” Cola said. “Data centers and AI mean chips are operating more like Michael Jordan’s shoes, rather than, say, my 12-year-old daughter’s.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

The Full Energy Picture

As Mahajan advocates looking at the full picture of the “stack,” a group of Georgia Tech engineers, economists, and policy scholars at the Strategic Energy Institute’s Energy Policy and Innovation Center (EPICenter) are looking at the full picture of energy.

Their goal is to understand the landscape of growing electricity demand across Georgia — driven in part by more data centers — to help policymakers and power companies plan.

“If you look at the numbers, we can’t meet future needs through adding a few power plants to the grid or increasing electrical efficiency,” said Steve Biegalski, professor and chair of the Nuclear and Radiological Engineering and Medical Physics Program in the Woodruff School. “We’re looking at a multi-decade strategy for the state of Georgia and the region, identifying technology readiness for everything that might be available today versus 20 years from now to figure out the best path of meeting demand while maintaining grid resilience.”

Though Biegalski has spent his career focused on nuclear energy and been an advocate for the value of nuclear power, he said there’s no denying that exploding growth of power-hungry data centers has sparked renewed interest in putting more nuclear power on the grid and exploring advanced reactor designs.

It’s fortuitous timing for a project Biegalski and some of his colleagues started formulating a decade ago to build a new kind of advanced nuclear reactor. They received a license in 2024 from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and, this year, support from the U.S. Department of Energy to construct and operate a molten salt research reactor in Texas.

Molten salt designs produce less nuclear waste and have built-in safety features that naturally slow or stop nuclear reactions without human intervention. It is privately funded by Natura Resources; Georgia Tech is part of the Natura Resources Research Alliance, a consortium with Abilene Christian University, Texas A&M University, and the University of Texas at Austin. Biegalski said the first molten salt reactor should be finished in the next year or so and will be an important step toward larger commercial systems.

Steve Biegalski (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

He was recently at a meeting of nuclear energy researchers and industry colleagues, and one of the presentations came from the data center lead at a large tech company. The presenter noted the company didn’t favor one source of electricity over another to power their AI data centers.

But their analysis was clear: They couldn’t meet their energy needs without nuclear energy in the mix.

“I’ve always believed that we needed nuclear power and that it has a lot of value, even if we weren’t in the midst of this huge push for data centers,” Biegalski said. “But it is the gorilla in the room. It’s huge demand, and you can’t get away from it.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

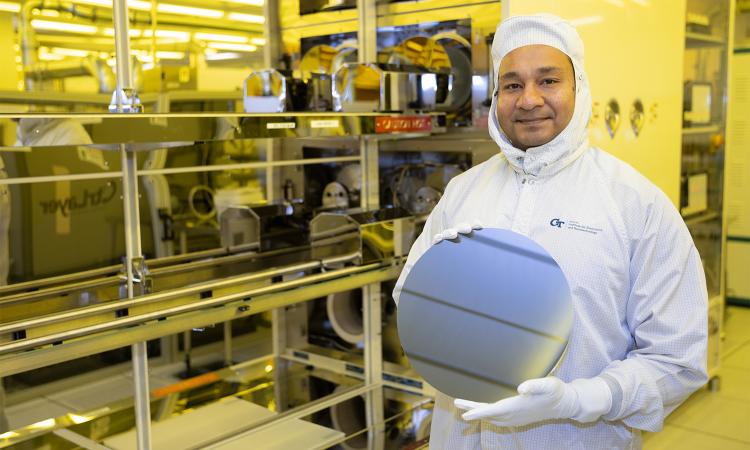

Engineering Next-Gen Computing

At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.

Digital Doppelgängers

Engineers are building computerized replicas of cities, and even Georgia Tech’s campus, to save lives and create a better, more efficient world for all of us.

Wearing the Future

From smart textiles to brain-computer links, Georgia Tech engineers are designing wearables that connect humans and machines more closely than ever to sense, respond, and heal.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Helluva Engineer

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Helluva Engineer magazine.

The future of computing isn’t just about making chips smaller or faster; it’s about making computing better for people and society. And Georgia Tech engineers are shaping that future, designing the processors and memory that will power technologies we can’t yet imagine. They’re using today’s digital power to shape the physical world, helping people live healthier lives, making cities safer, and addressing the digital world’s huge demands on real-world land and resources. Smaller, smarter, faster — the pace of change in computing is accelerating; log into our latest issue to see how Georgia Tech engineers are making it all add up.