How we get around is changing as new options like autonomous vehicles arrive in earnest. Srinivas Peeta works to unravel what that means for our communities and how we plan for a more connected future.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

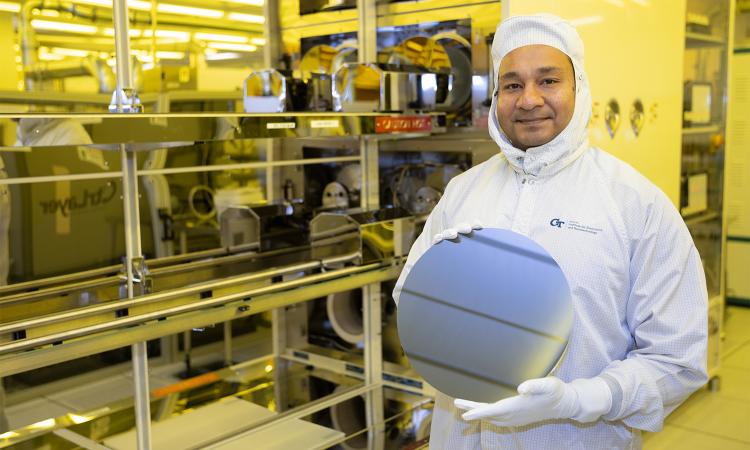

Srinivas Peeta in his driving simulation lab. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

If we’re moving toward a future where most vehicles drive themselves, the road between here and there has more than a few potholes. Some are becoming clear; others wait around the next bend. All require careful maneuvering to keep people and communities safe.

Georgia Tech civil engineer Srinivas Peeta is leading the road crew filling holes, repaving streets, and preparing for a future where our vehicles — and the infrastructure around them — are smarter and more connected.

“Connected and autonomous vehicles are, in many ways, transformative — and disruptive as well,” said Peeta, Frederick R. Dickerson Chair and professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering. “So there are many problems or questions that are of interest to us.”

One immediate issue: the friction between human drivers and the autonomous cars starting to appear in some parts of the country. For example, Waymo started offering rides in self-driving cars earlier this year to Atlanta Uber users. The cars rely on sensors, training data, and programmed rules. Human drivers rely on none of this, instead depending on situational awareness, experience, and context. It’s a mismatch that can lead to conflict.

[Autonomous] cars rely on sensors, training data, and programmed rules. Human drivers rely on none of this, instead depending on situational awareness, experience, and context. It’s a mismatch that can lead to conflict.

Conflicts on the Roads

Peeta’s team studies those interactions to understand what situations will show up as autonomous vehicles expand and how to address them.

One example is platooning, where self-driving cars and trucks travel close together on highways at high speeds. That can make it more difficult for drivers to change lanes or merge, leading to frustration or risky behavior.

Or consider handoff scenarios, when a partly autonomous vehicle encounters a situation too complex to handle and requires the human driver to take over. That driver might be distracted — maybe they were reading, watching a movie, talking with another passenger — and the sudden need to reengage can pose safety risks.

Peeta suggested other kinds of conflicts could actually make roads safer. For example, his team is studying lane-change scenarios where a self-driving car could block a dangerous maneuver by a human driver.

“We are looking at scenarios where autonomous vehicles determine when to assist and when to prevent lane changes, because there may be lane changes that are really dangerous, especially on freeways,” he said. “What the vehicle would do is preclude that lane change, preventing the person from making it to enhance safety.

“Of course, aggressive drivers may get frustrated, so there are other consequences that may show up. You have to figure out all of these possibilities.”

Security is another concern. Peeta and his team have been testing whether drivers can spot a compromised autonomous vehicle on the road.

What tips them off? And then: how do they react?

Using a full-size driving simulator in their lab, analytical models, and real-world data collection — including a partnership with the City of Peachtree Corners northeast of Atlanta — his team examines how humans and the vehicles interact, how vehicles deal with infrastructure, and how infrastructure influences human behavior.

More autonomy on our roads likely will mean roads look different in the future, Peeta said. And in the meantime, we might need to adjust road designs to help drivers and autonomous vehicles coexist more smoothly. Peeta and his team have built a computer model of a part of Peachtree Corners called a digital twin to test potential layouts.

“What we found is that some designs are more intuitive for human drivers to figure out the intent of these autonomous vehicles,” he said. “Sometimes they’re more cautious. Sometimes they’re not sure what they have to do. Human drivers might wonder, why is this slowing down here when other vehicles would nicely zip off? Some road designs make it easy for human drivers to understand how autonomous systems drive.”

Connected Communities

Autonomous vehicles are just one piece of a changing transportation landscape. Ride-sharing, micromobility options like scooters and bikes, and autonomous shuttles are becoming more common.

Peeta’s team is deep into a National Science Foundation project to understand how these new technologies can work together with traditional transit and personal vehicles to achieve a community’s mobility goals.

“These are showing up organically. The question is, how does a city leverage all of these in a systematic way where they’re integrated,” Peeta said. “That allows for strategic decision-making, rather than doing trial and error without the convergence that can be enabled by looking at all of it holistically.”

The goal is a system that improves safety, public health, and access to jobs and services while mitigating environmental effects like air pollution. One component focuses on how information influences people’s behavior — including how to deliver the right information to the right people at the right time.

Srinivas Peeta (standing) and Ph.D. students Gulam Kibria and Yangjiao Chen prepare driving scenarios for their driving simulator. (Photo: Candler Hobbs)

The result will be a dashboard-like tool that pulls in all of the data available to cities to help them build the transportation networks that work for their residents. It’s designed to be flexible, Peeta said, because what works for a suburban, well-connected area probably won’t for a low-income or rural area. And priorities change over time. His tool will allow planners and decision-makers to adjust.

“What we’re looking at is fostering more travel that’s sustainable. That is, to try to get people to use options that are more friendly to themselves or the environment that also simultaneously improve mobility and safety,” Peeta said.

“Every community will have its own needs, its own resources, and it will be able to use our framework to come up with the best cocktail of options.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

Engineering Next-Gen Computing

At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.

Digital Doppelgängers

Engineers are building computerized replicas of cities, and even Georgia Tech’s campus, to save lives and create a better, more efficient world for all of us.

Wearing the Future

From smart textiles to brain-computer links, Georgia Tech engineers are designing wearables that connect humans and machines more closely than ever to sense, respond, and heal.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Helluva Engineer

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Helluva Engineer magazine.

The future of computing isn’t just about making chips smaller or faster; it’s about making computing better for people and society. And Georgia Tech engineers are shaping that future, designing the processors and memory that will power technologies we can’t yet imagine. They’re using today’s digital power to shape the physical world, helping people live healthier lives, making cities safer, and addressing the digital world’s huge demands on real-world land and resources. Smaller, smarter, faster — the pace of change in computing is accelerating; log into our latest issue to see how Georgia Tech engineers are making it all add up.