As an electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. student, Edgar Garay reimagined how chips called power amplifiers could work. His startup company based on that innovation has raised millions in capital to disrupt a $23 billion dollar industry where designs haven’t changed much in decades.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Small chips you’ve probably never heard of are at the heart of every wireless communications device. These power amplifiers are embedded in our smartphones, cellular towers, satellites and satellite receivers, and much more.

If a digital device has an antenna, it has power amplifiers. And they are absolute energy gobblers.

Just powering our mobile phone infrastructure costs tens of billions of dollars in electricity every year. A good chunk of your phone’s battery life goes to these tiny chips, which are responsible for amplifying digital signals so the phone can communicate with a nearby tower.

Edgar Garay knew there had to be a way to cut down on the energy used and the heat produced in the process. He came to Georgia Tech for his doctoral studies laser-focused on the problem. Now he’s founder of an Atlanta-based company called Falcomm with $12 million in startup funding, around two dozen employees, and customers ready to deploy the technology he created to address a problem more or less ignored for decades.

“Every device that you own has 10, 20, sometimes hundreds of power amplifiers. The power amplification process consumes a lot of energy and is very inefficient,” said Garay, who earned his electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. in 2023. “While working at Georgia Tech, I figured out how to do it twice as efficiently as any other power amplifier in the world.”

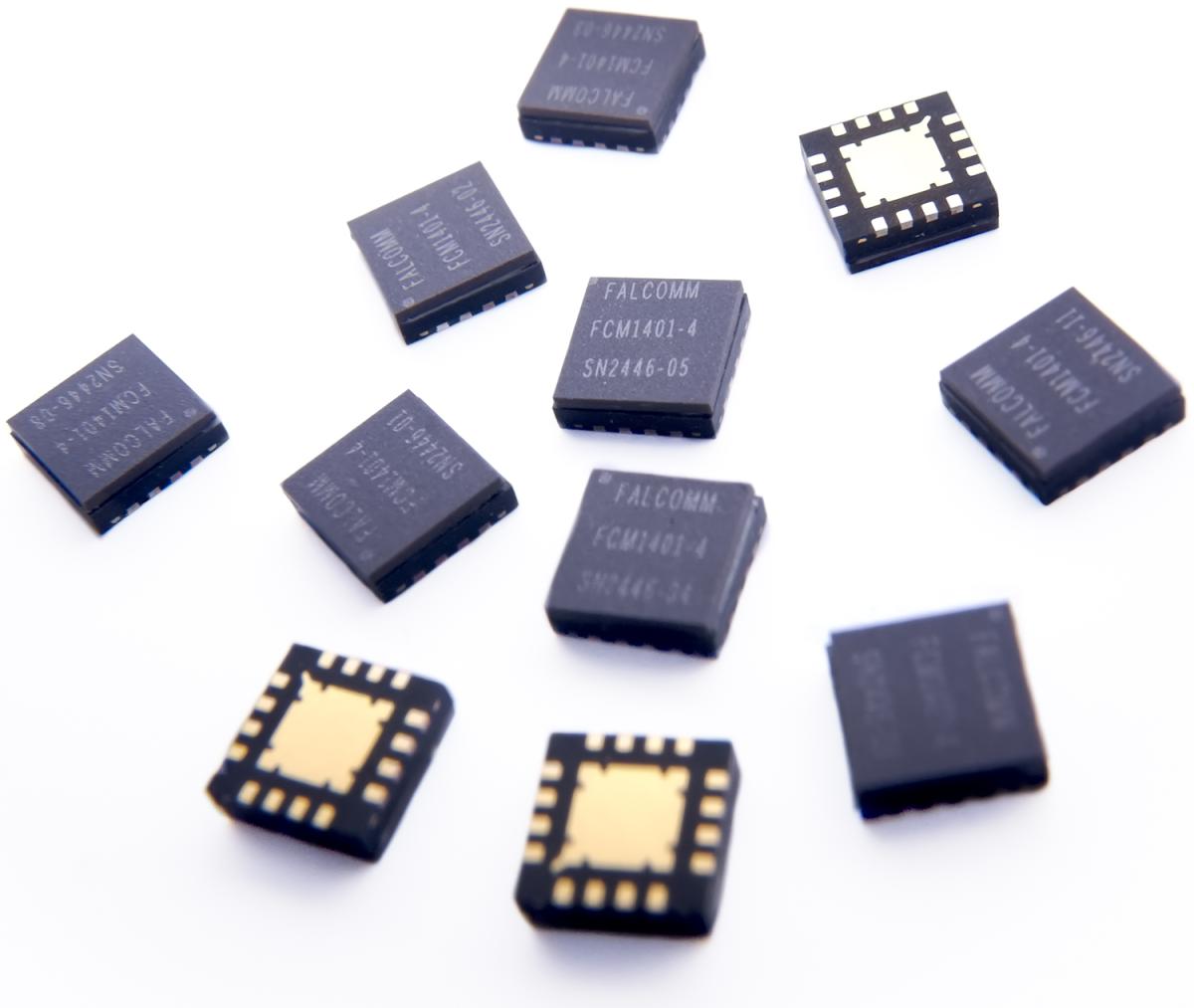

The Falcomm power amplifier is half the size with nearly twice the energy efficiency of existing chips. (Courtesy: Falcomm)

Garay didn’t create a new material or process. Instead, he started at the transistor level to redesign the architecture of the power amplifier chip. His “dual drive” approach splits the radio frequency signal, delivering nearly two times the energy efficiency at double the power with chips that are half the size. Bottom line, Falcomm says: more power, less heat.

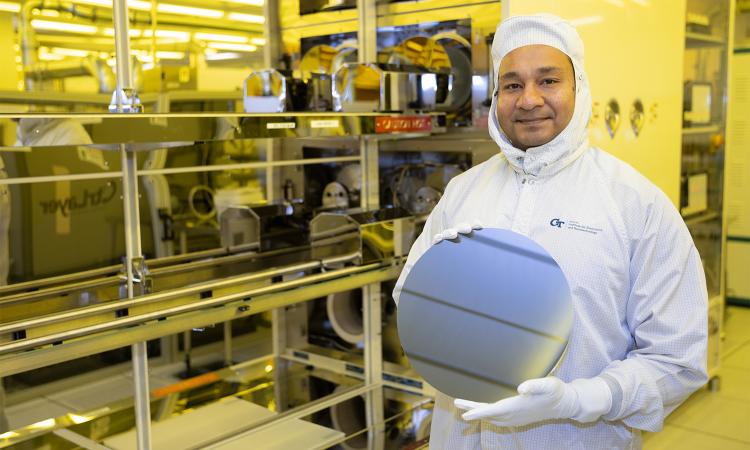

And because the innovation is in the architecture of the chip, Garay’s designs can be manufactured by existing commercial semiconductor foundries.

“We don’t have to spend money on expensive materials or exotic manufacturing processes to get just 5% improvement in technical performance,” he said. “We can use manufacturing processes that already exist. And after three months, you have a super high-performing power amplifier that beats all the energy efficiency records of existing hardware.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Garay didn’t create a new material or process. Instead, he started at the transistor level to redesign the architecture of the power amplifier chip. His “dual drive” approach splits the radio frequency signal, delivering nearly two times the energy efficiency at double the power with chips that are half the size.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

When Garay first developed his chips, he partnered with a commercial foundry to create the prototypes. His contacts there were so impressed with the results, they encouraged him to think about creating a company around the technology. He tapped into Georgia Tech’s commercialization resources, including VentureLab and CREATE-X, and he built his entrepreneurial skills in an incubator program at the University of California, Berkeley. A couple of years ago, Falcomm became the first startup supported through Tech’s Research Impact Fund, an investment fund targeted to companies based on Georgia Tech intellectual property.

Falcomm’s first paying customers were satellite manufacturers and aerospace companies — firms building out space infrastructure where thermal management and energy efficiency are at a premium. Garay said it’s a problem Falcomm is perfectly positioned to solve, even if it took some convincing initially.

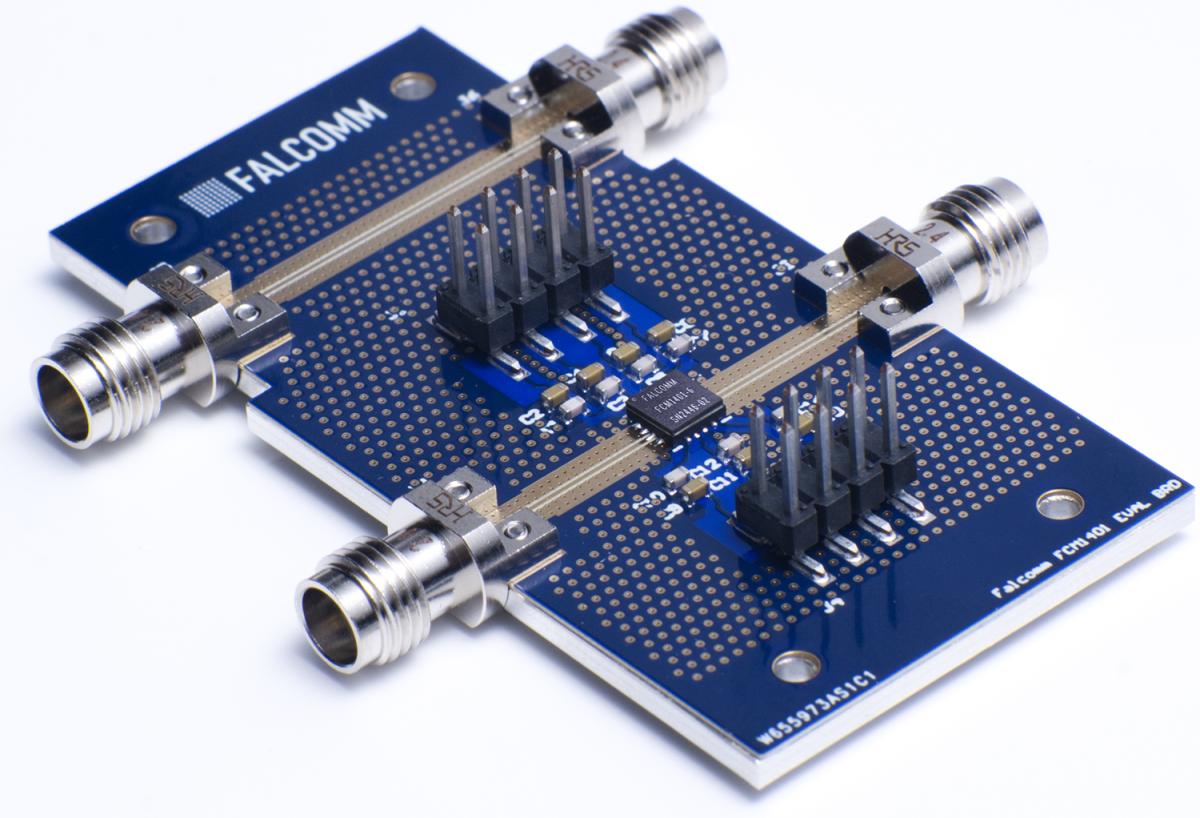

The power amplifier connected to an evaluation board for performance tests. (Courtesy: Falcomm)

“When we started showing our performance numbers to satellite manufacturers, their first reaction was, ‘We don’t believe the numbers. There’s no way,’” Garay recalled. “I asked if that was because our numbers are bad. Quite the opposite. They told me they were amazing.”

As Garay and his growing team keep working on their solutions, they’re also finding that the software tools they use to design semiconductor chips don’t work as well as they want. No sweat: Falcomm has been adding software engineers to its team of chip designers so they can innovate on the design tools themselves, too.

For now, Falcomm is a “fabless” company, meaning they create designs to meet customers’ specifications and send them to foundries for manufacturing. But if Garay has his way, that will change in the next few years. He envisions setting up a foundry in Atlanta as part of a groundswell of semiconductor design and manufacturing.

“We’re building relationships with venture capitalists and the government, because this can be a good partnership between public and private capital to create jobs and create a semiconductor ecosystem in Atlanta. We have the talent,” Garay said. “Our four- or five-year vision is to go from fabless to doing 100% of our fab right here in Atlanta.”

With four patents and 13 more applications pending, two rounds of investment from Georgia Tech, and millions of dollars from other investors, Garay and his team seem to have hit on an area that was ripe for creative problem-solving. He’s not surprised.

“We’ve been using the same power amplifier architecture for the past 90 years. I realized there had to be a better solution.”

(text and background only visible when logged in)

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Related Stories

Engineering Next-Gen Computing

At Georgia Tech, engineers are finding new ways to shrink transistors, make systems more efficient, and design better computers to power technologies not yet imagined.

Better, Not Just Bigger

The massive computing facilities popping up across the country have become notorious for requiring huge resources. Our engineers are thinking about how data centers can be more efficient and how they influence our future power needs.

Wearing the Future

From smart textiles to brain-computer links, Georgia Tech engineers are designing wearables that connect humans and machines more closely than ever to sense, respond, and heal.

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Helluva Engineer

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Helluva Engineer magazine.

The future of computing isn’t just about making chips smaller or faster; it’s about making computing better for people and society. And Georgia Tech engineers are shaping that future, designing the processors and memory that will power technologies we can’t yet imagine. They’re using today’s digital power to shape the physical world, helping people live healthier lives, making cities safer, and addressing the digital world’s huge demands on real-world land and resources. Smaller, smarter, faster — the pace of change in computing is accelerating; log into our latest issue to see how Georgia Tech engineers are making it all add up.